The nurse checked the monitor again.

“Your labs showed several medications in your system, ma’am. We’re still going through the full panel. Some of them don’t play nicely together.

The doctor will go over everything.” She hesitated, choosing her words with care. “Do you remember what you took before bed?”

The mug burned in my memory.

“My daughter-in-law made me something to help me sleep,” I managed. My voice sounded like it had scraped against gravel on the way out.

“What was in it?”

“She said it was…just something stronger than herbal tea.” My throat tightened.

“I didn’t ask the name. That was foolish of me.”

The nurse didn’t comment, but something in her expression changed. Not shock.

Something closer to cautious recognition. She’d seen this pattern before.

People like to believe poison arrives in dramatic ways. A stranger.

A threat. A crime show.

They never picture a mug in their own kitchen.

By the time the doctor came in, I had pieced together fragments of myself. My name was Martha Eldrich.

I was seventy-one years old. I’d been a widow for nearly a decade. I’d spent thirty years working nights as a registered nurse at Riverside General before retirement, which meant I knew exactly how many drugs you had to mix to kill someone.

Apparently someone had tried.

The doctor was in his early fifties with a wedding ring and the tired eyes of a man who’d delivered too much bad news and never gotten used to it.

His badge read DR. K. HARRISON.

He pulled the curtain partway closed and took the chair by my bed.

“Mrs. Eldrich,” he said, folding his hands. “I want to go over what we found in your bloodwork so we’re on the same page.”

I nodded.

The monitor clipped my heartbeats into neat little blips.

“You had three sedating agents in your system,” he said. “One is a prescription sleep medication that is, according to your chart, prescribed to you. The second is an antihistamine at a dosage we don’t typically recommend for your age.

The third is an opioid.” He paused, letting that land. “The level of the sleep medication—Zolpidem—was over five times the usual therapeutic dose.”

Five times.

The number dropped into my chest like a stone into deep water.

“I would never take that much on my own,” I said, my voice sharper than it had been all morning. “I’m careful.

I was a nurse for three decades. I’m obsessive about dosages.”

His gaze didn’t leave my face. “I believe you.”

“Then how—”

“The way these medications were combined and dosed, it’s…too precise to be an accident,” he said quietly.

“This goes beyond mixing up pills in a weekly organizer.”

My skin went cold.

He glanced toward the door, then back at me. “Hospital protocol requires us to notify authorities when there’s a reasonable possibility of intentional or negligent poisoning, especially in vulnerable adults. That process has already started.

An investigator from the Columbus Police Department will be coming by to speak with you.”

The word poisoning slid into the space between us and sat there, heavy and unreal.

“Doctor,” I whispered, “my daughter-in-law gave me that drink. She…she’s sharp sometimes, impatient. But she wouldn’t…” I swallowed.

“She’s the mother of my granddaughter. My son loves her.”

I had spent so many years filing down other people’s sharp edges in my mind, telling myself they didn’t mean it. That they were tired or stressed or just not raised to say thank you.

He didn’t contradict me.

“Right now, our job is to keep you safe and document what happened,” he said. “The police will determine intent. In the meantime, I want you to rest.

You’re out of the immediate danger zone, but your system went through a lot.”

He stood. For a heartbeat, I wanted to reach out, to grab his sleeve and drag him back to the bed like patients used to grab mine when I tried to leave their rooms at night.

Because rest sounded like the cruelest prescription of all.

How was I supposed to rest when the last person to hand me a mug of something warm had almost stopped my heart?

The investigator arrived late that morning. By then I had made it through a nurse’s shift change, a sponge bath, and one visit from a case manager with pamphlets about fall prevention I hadn’t asked for.

He did not look like the detectives on television.

No trench coat, no square jaw, no brooding silence. He was a little stooped, with thinning gray hair and kind eyes that looked like they’d seen too much and were still trying to stay soft.

“Mrs. Eldrich?” he asked from the doorway, lifting his badge.

“I’m Detective Daniel Hail with Columbus PD. Mind if I come in for a few minutes?”

I had spent my life telling patients that everything would be okay if they just breathed through the next ten seconds, the next minute, the next needle. I practiced my own advice.

“Come in,” I said.

He took the same chair the doctor had used and opened a small notebook.

No laptop. No recorder I could see. Just paper and pen.

“I’m sorry to meet you under these circumstances,” he said.

“I’ll try not to tire you out. I just need to understand what happened last night, in your own words. Take your time.”

My hands twisted the edge of the blanket.

I forced them to be still.

“Start wherever it makes sense for you,” he added.

“The kitchen,” I said. “Last night. Around nine.

Maybe nine-thirty.”

He nodded and waited.

“I couldn’t sleep. I’ve had trouble since…my husband, Thomas, passed,” I said. “I lit one of those lavender candles Lily got me for Christmas.

I was rinsing my mug from chamomile tea, and Clara walked in.”

“Clara is…?”

“My daughter-in-law.” The word tasted complicated. “She’d been staying with us more lately. With me.

My son works late at the accounting firm downtown. She handles most of Lily’s school stuff, so she’s in and out of the house constantly anyway.”

“What was her mood like?” he asked.

“Tight,” I said before I could soften it. “Controlled.

The way she gets when she’s already irritated and trying to look generous.”

He scribbled something down.

“She told me she’d noticed I was dragging,” I continued. “That I was up when she got home, that I looked exhausted at dinner. She said, ‘Mom, you can’t keep doing this.

You’re going to make yourself sick.’”

“And then?”

“She said she had something stronger than herbal tea,” I said. “Something the pharmacist recommended. She turned her back to me, mixed it at the counter.

I couldn’t see the labels from where I sat.”

I could see the mug, though. It was white with a small chip on the rim in the shape of Ohio, a Mother’s Day gift from David ten years ago. The steam curled up and carried the scent of honey.

“And a bitterness under it,” I added quietly.

“I noticed it. I told myself it was just the medication.”

“Did she tell you what she put in it?”

“No.” The word came out like a confession. “And I didn’t ask.

I was tired. I wanted to sleep. I told myself she’d checked, that she knew what she was doing.

She’s not medically trained, but she’s bright. Organized. She prints out everything she finds online.”

Hail nodded again.

“Did you take any other medications on your own?”

“I took my regular heart pill with dinner,” I said.

“Metoprolol. Low dose. I’ve been on it for years.

I took my prescribed Zolpidem at nine, like always. I did not add anything else.” My jaw clenched. “I don’t double-dose.

I’ve watched too many patients stop breathing to play games like that.”

“You were a nurse, correct?”

“For thirty years.”

He wrote that down, then lifted his eyes to mine. “I’ll ask this as plainly as I can. Do you believe your daughter-in-law intended to harm you last night?”

The question punched the air from my lungs.

Because the answer wasn’t a simple no.

If he’d asked me that question ten years earlier, I would have laughed, offended on Clara’s behalf.

Her flaws back then were impatience and a sharp tongue, not malice. She worked in marketing. She brought over store-bought casseroles and posted smiling pictures of the three of them on Instagram.

Somewhere between then and now, something had shifted.

The smiles had grown more polished. The comments toward me had grown barbed. The space that used to be mine had been quietly rearranged.

“I don’t know what I believe yet,” I said finally.

“She’s family. I know she doesn’t like the way I do things. I know she thinks I’m stuck in the past.

I know she thinks I should sell the house and move into one of those senior communities with bingo nights and water aerobics.”

My throat tightened.

“I also know she watched me drink every drop in that mug and didn’t ask me once how I felt afterward.”

He didn’t rush to fill the silence.

“The toxicology panel we ran overnight,” he said after a moment, “shows three medications, one of them at over five times a typical dose for someone your age and weight. That level is not something a person reaches by accident. Somebody measured it out.”

There it was again.

“One of my jobs,” he added, “is to figure out who had access to those medications and who stood to gain from you being incapacitated or…gone.”

I flinched.

He noticed.

“We’ll need a formal statement later,” he said more gently.

“For now, I’m going to ask your son some questions as well. Rest as much as you can, Mrs. Eldrich.

I know that’s a strange thing to ask after all this.”

He closed his notebook with a quiet click.

“Detective?” I asked as he rose. “Will you be speaking with Clara today?”

“Yes,” he said. “Separately.”

Separately.

The word shouldn’t have comforted me.

It did.

David arrived just after lunchtime, bringing a gust of cold February air in with him.

My son was forty-four, but in that moment he looked like the exhausted boy I used to pick up from soccer practice when the Ohio wind had turned his cheeks raw.

His shoulders were hunched inside his gray suit jacket. His tie was knotted crookedly. His dark hair, usually neat for clients and partners, looked like he’d been raking his fingers through it on the drive over.

“Mom,” he said, voice cracking as he came to the side of the bed.

“Jesus. Don’t ever do that to me again.”

I almost laughed. As if I’d scheduled this.

“I didn’t plan a field trip to the ICU, David,” I said.

The words were dry, but my hand shook when I reached for his. He took it in both of his own, as if anchoring himself.

“What happened?” he asked, eyes darting over my face, to the monitor, to the IV pump. “The detective called me.

He said…he said they found…”

“Too much of the wrong things in my blood,” I finished for him. “Your wife made me a drink before bed.”

He went pale in a way I had only seen once before—when Thomas’s cardiologist told us his heart was failing faster than they’d expected.

“Clara?” he whispered.

I could have softened it. I could have said, She tried to help.

I could have handed him an excuse to hold on to.

Instead, I told him the truth.

“She said it was something mild from the pharmacist,” I said. “She turned her back while she mixed it. I didn’t see what she put in.

I tasted something bitter. I drank it anyway. An hour later I was on my bedroom floor, and that’s where you found me, I assume.”

His grip tightened painfully.

“I thought you’d had a stroke,” he said.

“You weren’t answering your phone, and Lily was panicking. You were breathing so shallow I could barely see your chest move.” His voice broke. “I called 911 from the hallway and tried to keep her from seeing too much.”

Lily.

My fourteen-year-old granddaughter with her messy bun and permanent smudge of ink on her fingers from sketching. The idea of her watching paramedics work over my body made my stomach twist.

“Did Clara call 911?” I asked.

He hesitated, just long enough to answer.

“No,” he said. “She said she thought you were just sleeping deeply.

She told the paramedics that, too.”

I closed my eyes.

Of all the tiny kindnesses I’d given that woman over the years—rides, babysitting, meals, excuses—that was the one I wished I could take back: my benefit of the doubt.

“Detective Hail told me the doses couldn’t have been accidental,” I said quietly. “He’s not using the word lightly.”

David’s jaw clenched. “He told me the same thing.” He scrubbed his free hand over his face, fingers pressing into his eyes.

“They found blister packs in the bathroom cabinet that aren’t prescribed to you. Or me. Or Lily.

He asked me if I recognized the name on the label.”

“Do you?”

“Yeah,” he said, a humorless laugh catching in his throat. “It’s on one of Clara’s old bottles from when she was having trouble sleeping after Lily was born. I thought she’d gotten rid of the extras years ago.”

My heart didn’t lurch this time.

It settled.

“David,” I said.

“Look at me.”

He did. His eyes were red, but steady.

“I’m not asking you to choose sides yet,” I said. “I know you love your wife.

I know you want to believe this is all some awful misunderstanding.”

He swallowed.

“But I am asking you to stop talking yourself out of what you can see,” I finished. “The dosages. The missing pills.

The way she talks about me when she thinks I’m not listening.”

A muscle jumped in his cheek.

“I hear her,” I added. “She forgets how thin the walls in that house are.”

He dropped his gaze to our hands. “I should have listened sooner,” he whispered.

The monitor at my side kept beeping, calmly counting off the seconds in which my son’s life was rearranging itself.

They kept me one more night for observation.

Nurses came and went. The tech woke me every few hours to check my vitals, apologizing each time. I told her not to.

Sleep and I were strangers long before this.

In the dark, I stared at the ceiling that wasn’t mine and thought about all the ways harm sneaks in through ordinary doors.

We expect danger on highways and late-night news reports, not in the person who rearranges our kitchen and calls it helping.

In the morning, after another visit from Detective Hail and a hospital social worker who asked me if I felt safe at home, the answer to that question finally settled inside me.

No.

“No, I don’t,” I told her. “But I’m not ready to leave it yet.”

She nodded. “Then we make the home safer,” she said, like it was as simple as installing a grab bar.

“The detective mentioned he’ll be in touch. Do you have someone you trust who can be with you when you go back?”

“My son,” I said. “My granddaughter.

My neighbor. And, apparently, a detective.”

She smiled faintly at that.

“I’ll add a note to your discharge,” she said. “And a referral for community resources.

Elder law attorneys. Support groups. This isn’t the first time we’ve seen a situation like yours, Mrs.

Eldrich.”

I believed her.

That knowledge comforted and enraged me at the same time.

The cab ride home was short and too quiet. It had snowed lightly overnight, leaving a thin powder on the lawns of our subdivision. The maple in front of my house wore a delicate white outline on its bare branches.

From the curb, my two-story colonial on Maple Glen Drive looked exactly the way it always had.

Blue shutters. Brick front. The concrete porch Thomas had insisted on sealing himself one fall.

Nothing had moved.

Everything had shifted.

I paid the driver, tipped more than I meant to, and stood on my front walk with the hospital discharge folder tucked against my coat.

My hand shook as I put my key in the lock.

Inside, the house smelled faintly of coffee and some citrus cleaner Clara liked. My slippers were no longer by the door but tucked neatly under the console table. The throw blanket I kept folded on the arm of the couch was draped in a way I never arranged it, like a catalog photograph.

My mail sat in a stack on the kitchen island, most of it already slit open.

I had not given anyone permission to do that.

I put my folder down and walked through each room, touching the back of each chair as if taking attendance.

In the hallway closet, my old wool coat was pushed to the back to make room for Clara’s jackets.

Beige. Camel. Black.

All expensive. All lined up in a neat row.

In the guest room—the one that used to be David’s when he was a boy—a suitcase lay open on the chair, half filled with Clara’s clothes. A silk blouse hung from the bedpost.

She’d planned to stay.

In my bedroom, the nightstand drawer gaped a fraction of an inch.

I never leave it like that. Inside, my prescription bottles stood in a row. Their positions were wrong.

Years of muscle memory told me so. The blood pressure pill had moved to the far right. The mild over-the-counter sleep aid was in the middle.

The Zolpidem was there.

The new bottle the hospital pharmacy had provided was still inside the plastic bag from discharge.

The old bottle—the one I’d taken from for months—was gone.

I stared at the empty space where it should have been.

A chill moved across my scalp.

Later, when I thought about that moment, what unnerved me wasn’t the missing bottle itself.

It was how easily, on any other day in the last few years, I might have told myself I’d misplaced it.

I was standing at the kitchen counter with the kettle whistling when the front door banged open without a knock.

“Grandma?”

Lily’s voice cut through the house like sunlight through a cloud.

She barreled into the kitchen with her backpack still slung over one shoulder, cheeks red from the February wind.

“Dad said you were home.” She dropped the backpack and wrapped her arms around me before I could answer.

“I told him I needed to see you before I went back to school. I don’t care if I’m late to geometry.”

I hugged her back carefully, breathing in the smell of pencil shavings and wintergreen gum.

“I’m all right,” I murmured into her hair. “A bit wobbly, but all right.”

She leaned back to study my face.

Fourteen going on forty, that girl. Thomas used to say she had my eyes and David’s stubborn chin.

“Grandma,” she said quietly, “I heard them fighting last night.”

My heart picked up a notch.

“Your parents?”

She nodded. “Dad and Mom.

In the kitchen. I was supposed to be in bed, but the walls in that house are like paper.” A sad little smile curved her mouth. “Dad has your voice when he’s mad, you know.

Quiet and sharp. He asked her why she waited so long to call 911.”

My chest tightened.

“What did she say?”

“She said she didn’t think it was that serious,” Lily said. “That you always exaggerate how dizzy you are.

That you’ve…imagined things before.” The girl’s jaw clenched so tight her braces flashed. “Dad got really angry. I’ve never heard him talk to her like that.

He said, ‘My mother’s heart stopped, Clara. Do you really want to stand here and blame her?’”

I gripped the edge of the counter to keep my legs steady.

“Lily,” I said, “you shouldn’t have to hear those things.”

“I’d rather hear the truth than lies,” she replied simply.

She was fourteen, but in that moment she sounded older than all of us.

“I don’t believe her,” she added. “About you exaggerating.

I’ve seen the way she talks down to you. The way she moves your things and says you forgot. You don’t forget, Grandma.

You notice everything.”

I blinked hard.

Children see more than adults give them credit for.

“Will you be okay here alone?” she asked.

“Yes,” I said. “And if I’m not, I have neighbors. And a detective with my address on file.” I tried to make it sound like a joke.

She didn’t smile.

She hugged me again, fierce this time.

“If she comes by,” Lily whispered into my shoulder, “you don’t have to let her in.”

When she pulled away, her eyes were suspiciously bright.

“Go to school,” I told her softly. “Ace your geometry test. Let your dad worry about the rest for once.”

She nodded, grabbed her backpack, and left with one last look over her shoulder.

The house felt different the second the door closed.

Less haunted.

More mine.

For the first time in years, I walked through my own home not as a guest trying not to be in the way, but as someone taking inventory.

The hall closet told me one story.

The guest room told me another. The kitchen drawers were a third chapter altogether.

The utensil drawer was rearranged—my spatulas shoved to the back, new silicone ones in bright colors where my wooden spoons used to be. My handwritten recipes sat under a glossy stack of printouts Clara had left in a binder titled “Updated Meal Plan for Mom.”

Mom.

The word didn’t bother me.

The rest did.

In the junk drawer by the fridge, the one every house has, I found three empty blister packs shoved under the tape dispenser. Generic Zolpidem. Ten-milligram tablets.

Not my pharmacy. Not my label. I turned one over and saw the imprint of Clara’s name faintly on the cardboard where it had been peeled away.

Evidence doesn’t shout.

It whispers.

I straightened, my knees popping in protest, and closed the drawer.

That was when the doorbell rang.

Followed immediately by three brisk knocks.

Not David’s rhythm.

Clara’s.

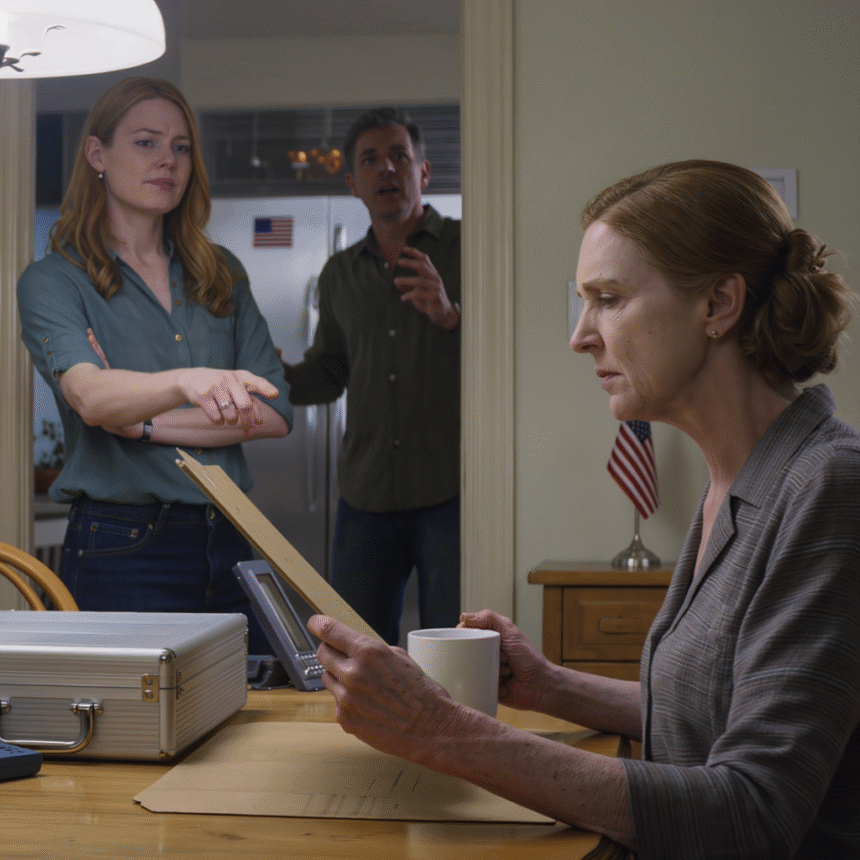

I opened the door only as far as the chain allowed.

She stood on the porch in a camel coat and heeled boots, her blonde hair scraped into a sleek knot. No makeup, which somehow made her look harder, not softer.

“Martha, thank God,” she said, though her eyes did not reflect gratitude. “David told me they let you out.

I rushed right over.”

She reached for the door to push it wider. I didn’t move. The chain held.

“You’re up,” I said.

“You must have had a late night.”

Color rose in her cheeks.

“They kept me at the station for hours,” she snapped, dropping the pretense of concern. “Asking the same questions over and over. Acting like I’m some criminal because I tried to help you sleep.”

“You didn’t call 911,” I said.

Her eyes flicked to mine and away.

“I thought you were resting. Your breathing has been shallow before. You said it’s normal with your heart.” She gave a tight little laugh.

“You of all people should know not every weird breathing pattern is an emergency, right? Nurse and all.”

I unhooked the chain and opened the door fully, stepping aside enough for her to enter without touching me.

She swept past, scanning the living room with the practiced eye of someone checking whether anything had been moved without her permission.

“Look at this place,” she said, scooping up my opened mail and setting it in a neater stack. “It’s good I’ve been keeping an eye on things.

You let everything pile up.”

“You opened my bank statement,” I said.

She didn’t even blink. “You get confused by those lately. Remember when you thought there was a fraud charge and it was just your electric bill?”

“That was three years ago,” I said.

“And there was an actual fraudulent charge on the next month’s statement that you told me not to ‘obsess about’ because it was only forty dollars.”

She shrugged, as if details bored her.

“Martha, we really don’t need to rehash old things right now,” she said. “What matters is that you tell the detective the truth.”

“What do you think I’ve told him?”

“That you’re tired,” she said quickly. “That you’ve been struggling to keep track of what you take.

That you probably doubled up without realizing. He needs to hear that this was a mistake, not…the other thing he keeps hinting at.”

“Poisoning,” I said.

She flinched at the word. “That’s a dramatic term for a dosage mix-up.”

“Five times the therapeutic amount isn’t a mix-up,” I replied.

“It’s math.”

She laughed then, the sound brittle. “There it is. The martyr tone.

You’ve always had it, you know. The poor-put-upon-nurse who gave her life to everyone else and gets nothing in return.”

“Clara,” I said quietly. “You rearranged my medications.

You opened my mail. You moved my insurance paperwork. You waited to call 911 while I was on the floor.”

Her eyes flashed.

“I was trying to help. No one else seems capable of keeping this place functional. You leave your pills everywhere, you forget where your savings book is, you—”

“I remember more than you think,” I cut in.

The silence that followed felt like new air in the room.

For the first time since she’d married my son, her face actually showed me something honest.

Annoyance.

“From now on,” I said, “you don’t open my mail.

You don’t step into this house unless I invite you. You don’t touch my medications, my bank statements, my keys, my mug. You don’t hand me anything to drink or swallow.

Not a vitamin. Not a cup of tea. Are we clear?”

Her mouth dropped open.

“You’re overreacting,” she said.

“The doctor said older adults get confused. You probably—”

“That line won’t work on me anymore,” I said, calm surprising even myself. “I’ve watched too many women get labeled confused the second they stop being convenient.

I am tired, Clara. But I am not confused.”

She stared as if I’d slapped her.

“David will never take your side,” she said softly. “He knows you blow things out of proportion.

He knows how you hold grudges.”

“He already has,” I said.

The way her shoulders jerked told me she believed me before her brain caught up.

“You’re going to ruin this family,” she whispered, grabbing her purse. “Over what? Over a mistake?

Over a night you barely remember?”

“No,” I said. “I’m finally refusing to let you ruin me.”

She marched to the door and yanked it open.

“This isn’t over,” she threw over her shoulder.

She was right.

But the part where I stayed silent was.

Detective Hail called that evening just as the sky outside my kitchen window turned the color of dishwater.

“Mrs. Eldrich?” he said.

“I wanted to let you know the full toxicology report is back.”

I tightened my grip on the receiver.

“The Zolpidem level we picked up in your blood was just over five times the usual therapeutic dose for you,” he said. There was no hesitation in his voice now. “Combined with the antihistamine and opioid traces, it created what we call significant respiratory depression.

If your son hadn’t found you when he did, we’d be having a very different conversation.”

“So it’s official,” I said. “It wasn’t a mistake.”

“There’s nothing accidental about that combination,” he replied. “We’ll be questioning Clara again tomorrow.

I’d recommend you keep your doors locked and consider asking a family member or friend to stay with you.”

I glanced at the deadbolt. At the chain I’d started using for the first time in my life.

“I’ll be careful,” I said. “Detective…if she altered any of my paperwork, legal or medical, is that something your department looks at or…?”

“That becomes part of a separate track,” he said.

“Elder financial exploitation. We work closely with the county prosecutor and sometimes with federal agencies depending on the amount. Why?”

My eyes drifted to the metal file box on the dining room chair.

“Because she’s been ‘helping’ me with my documents for years,” I said. “And I was stupid enough to think help always came without a price.”

“That doesn’t make you stupid,” he said. “It makes you trusting.

There’s a difference.”

After we hung up, I pulled the file box onto the table.

Most people keep their lives in cardboard boxes and plastic bins.

I kept mine in a gray metal file from Staples.

Medical records. Bank statements. Insurance policies.

An old power of attorney David and I had signed after my gallbladder surgery ten years earlier, in case I ended up in ICU again.

The power of attorney form sat near the bottom of the stack, separated into a manila folder. When I slid it out and opened it, my stomach turned.

I remembered signing two pages with David at a small law office near downtown. We’d gone in on a Wednesday morning, drunk burnt coffee from the lobby machine, and joked about how boring adulthood paperwork was.

The document in my hands had four pages.

My signature appeared on every one.

The strokes were mine.

The slant. The way my hand always dipped a little at the “th” in Martha.

But the ink on the last two signatures was darker. Fresher.

The clause above them talked about expanded authority over financial accounts in the event I was “temporarily or permanently incapacitated.”

I had no memory of signing that version.

I pressed my thumb to the paper. It came away clean.

My pulse pounded in my ears.

Evidence doesn’t always look like a smoking gun.

Sometimes it looks like an extra clause.

David came over after Lily’s bedtime, the fatigue of the day hanging off him like a too-heavy coat.

He sank into the dining chair across from me and stared at the open folders.

“Mom,” he said, voice rough. “I told the detective to check everything Clara has ever signed in your name.”

I slid the power of attorney toward him.

“Start here.”

He read the document once, frowning. Then again, with a different kind of focus.

“I don’t remember this clause,” he murmured. “We definitely didn’t go over this with Attorney Berman.

He was obsessively thorough.”

“We signed two pages,” I said. “I remember because I complained about how my hand cramped.”

His jaw clenched.

“I told Hail about the missing bank statement,” I added. “And the pharmacy receipt from the last time I picked up a sleep prescription.

It’s not in the stack. I remember the date. January fifteenth.

She went with me and made a comment in the car about ‘old people drugs.’”

David closed his eyes.

“Mom, she told the detective you’ve been forgetting things lately,” he said quietly. “She said you accuse her of moving items she never touched.”

“I spent thirty years charting every pill I gave a patient,” I replied. “I remember where I put my own bottles.”

He opened his eyes again.

For the first time since all of this began, there was no fog in them.

“I told him that,” he said. “I told him you’re meticulous. That you still correct my math when we split restaurant checks.”

A laugh bubbled up in my chest and surprised us both.

“We’re going to need help,” I said once it faded.

“Not just from the police. From someone who understands how to unwind whatever she’s done on paper.”

“I already called an elder law attorney,” he said. “Mrs.

Landon’s nephew recommended her. She can come by tomorrow if you’re up for it.”

I thought of my neighbor, watering her geraniums in summer and bringing casseroles when Thomas died.

“I’m up for it,” I said. “I’m too old to pretend I don’t need reinforcements.”

David scrubbed a hand over his face.

“She’s furious with me,” he admitted.

“She says I’ve betrayed her. That I’m choosing you over my own wife.”

“And are you?” I asked.

He looked at me across the table, his expression raw.

“I’m choosing the person who didn’t try to kill anybody,” he said.

It wasn’t the answer of a son choosing his mother.

It was the answer of a man choosing the truth.

I didn’t sleep much that night, but for once it wasn’t the frantic, hamster-wheel kind of insomnia that had plagued me since Thomas’s funeral.

It was a wired stillness.

I lay in my own bed beneath my own crack in the ceiling and listened to the furnace kick on and off. Every now and then, a car rolled past on Maple Glen Drive, the crunch of tires on salt and snow a familiar winter sound.

At two in the morning, I swung my legs out of bed and padded to the kitchen.

I boiled water for tea, my body moving through motions I’d done thousands of times.

Mug on the counter. Kettle on the stove. Tea bag in.

Water poured.

My hand hovered over the honey.

The last time I stood in this spot with steam curling from a mug, I’d ended up intubated.

I added the honey anyway.

Not because I trusted anyone.

Because this time, every bottle on the counter was one I had placed myself.

I sat at the table and wrapped my hands around the warm ceramic.

The mug was the same chipped white one David had given me for Mother’s Day all those years ago.

It had tried to kill me once.

Tonight, it was just a mug.

That was the difference.

Who controlled what went into it.

Evelyn Carile arrived the next afternoon carrying a leather briefcase and the kind of calm that doesn’t waver when someone raises their voice.

She was in her late forties, with dark curls pulled into a low bun, a navy blazer over a cream sweater, and sturdy boots dusted with salt from my driveway.

“Mrs. Eldrich,” she said, shaking my hand with a firm grip. “I’m Evelyn.

I’ve spoken briefly with Detective Hail and your son. I’m sorry you’re going through this, but I’m glad you called me when you did.”

We sat at the dining table, the same spot where I’d signed the original power of attorney years ago. I pushed the metal file box toward her.

“This is most of my life,” I said.

“The parts that fit in folders, anyway.”

She smiled faintly and opened the box.

For the next hour, she went through each stack with the patience of someone assembling a puzzle she already knew how to solve. Every gap in dates, every unexplained withdrawal, every pharmacy receipt that didn’t match my memory, she flagged with a sticky note.

When she reached the altered power of attorney, she took a little longer.

“Did you sign this version?” she asked.

“I signed a shorter one,” I said. “Two pages.

That’s all.”

She nodded, eyes tracing my signature.

“The handwriting is yours,” she said. “But see here?” She pointed to the last two signatures. “The pressure is different.

The strokes hesitate in places your earlier ones don’t. And there’s a slight halo in the ink where someone traced over the original line.”

“So she didn’t just add a clause,” I said. “She traced my name.”

“That’s my professional opinion,” Evelyn replied.

“It will likely be the handwriting expert’s as well.”

I exhaled slowly.

“What does that mean?”

“It means that document is tainted,” she said. “We will revoke it formally. Today.” She pulled new forms from her briefcase.

“We’re going to do three things, if you’re willing. First, we’ll revoke all prior powers of attorney and medical directives. Second, we’ll establish a new healthcare proxy and financial power of attorney you choose—someone you trust.

Third, we’ll set up a revocable living trust so your house and accounts are clearly protected.”

“Will that help the police?”

“It will keep Clara from doing any further damage,” she said. “And it will show the prosecutor you’re taking the situation seriously. But more importantly, it puts you back in control.

This is your life, your house, your future. Not a project for your daughter-in-law to manage.”

I hadn’t realized how much I’d needed to hear those words until she said them.

“Who do you want as your new agent?” she asked. “For medical decisions and finances if you’re ever incapacitated again?”

“David,” I said without hesitation.

“He made a mess of seeing what was right in front of him, but he never once touched my money without asking.”

“And if something happens to him?” she asked.

“Lily,” I said. “When she turns eighteen. Until then, the trust can name her as beneficiary.”

Evelyn smiled.

“I like the way you think.”

She slid the first document toward me and laid a pen beside it.

“You’re revoking the old forms with this one,” she said. “Once I file it, anyone who tries to use the tainted version will hit a wall.”

I read every line.

Thirty years of charting had trained me to scan for small words that changed big things—unless, except, until.

When I was satisfied, I signed.

My hand didn’t tremble.

By the time we finished, I had signed more pages than I had the day I married Thomas.

When Evelyn packed her briefcase to leave, she paused at the door.

“You know,” she said, “most people wait until everything has imploded before they call someone like me. You’re ahead of the curve.”

“I feel late,” I admitted.

She shook her head.

“You did what women of your generation were taught to do,” she said. “You trusted the people your son brought home. You gave the benefit of the doubt.

You kept the peace. That’s not a crime. But it doesn’t have to be your story from here on out.”

After she left, the house felt different.

The walls were the same.

The furniture hadn’t moved.

But my name had been written back into the foundation in a way no one could quietly erase.

The next two days blurred into a strange mix of normal tasks and sudden jolts of unreality.

I made oatmeal in the mornings. I folded laundry. I watered the fern in the bathroom that Clara hated because it “made the space feel cluttered.”

In between, my phone buzzed with updates.

Detective Hail calling to say Clara had retained an attorney and was refusing further questioning without counsel.

David texting that he’d moved into a friend’s guest room for now, that Lily was staying with a classmate’s family on the other side of town.

“She’s safe,” he wrote. “She misses you. We’ll come by tomorrow.”

Safe.

The word landed heavier than it used to.

Late in the afternoon on the second day, I stood at the front window with my mug of tea—plain chamomile this time, sweetened with a little honey—when I saw her.

Clara was across the street, half-hidden behind the Hendersons’ bare maple tree.

She wore a long black coat and no hat, arms crossed tight against the cold.

She wasn’t looking at the house directly.

She was looking toward it.

Watching.

The second she realized I’d seen her, she turned and walked quickly down the sidewalk, her boots sending up little puffs of powdered snow.

The tea in my hand cooled untouched.

For a long time, I would replay that image in my mind—not the hospital monitor, not the empty pill bottle, not even the forged signature.

Her standing under another family’s tree, furious and waiting.

Like the one thing she couldn’t stand wasn’t being accused.

It was being denied access.

David and Lily came the next day right after lunch. He knocked, this time, and waited for me to open the door.

It was a small thing, that knock.

It felt enormous.

He stepped inside with his shoulders squared the way they were when he walked into difficult meetings, Lily a step behind him.

“How are you?” I asked.

“Exhausted,” he said honestly. “But clear.”

Lily dropped her backpack on the floor and hugged me without a word.

We sat at the table together.

I poured tea. Lily took a can of soda from her bag instead and popped the tab with teenage defiance.

“I called a counselor,” David said. “One who specializes in families going through…this kind of thing.

I’m taking Lily next week. I’m going too. I don’t want her carrying this alone.”

I nodded.

“That’s wise.”

He rubbed his palms on his jeans. “The detective showed me some of their findings,” he said. “Internet searches on her tablet about sedative combinations.

Ratios. How long certain drugs stay in the bloodstream. Pharmacy purchase logs in her name.”

He stared at the table.

“I told myself for years she was just anxious,” he said.

“That she needed to control things to feel safe. I didn’t see how much controlling things meant controlling people.”

“Love makes us blind,” I said softly. “Fear keeps us that way.”

He looked up.

“I was afraid of being alone,” he admitted.

“Afraid of breaking up my daughter’s home. Afraid of being the guy who couldn’t make his marriage work. So every time you flinched at something she said, I smoothed it over.

I told you she was tired. I told myself you were sensitive.”

“I let you,” I replied. “That’s my part.

I could have pushed harder. I chose peace over truth too.”

He shook his head. “Except it wasn’t peace,” he said.

“It was a ceasefire you paid for.”

We sat in the quiet that followed.

Then Lily spoke.

“When I was little,” she said, eyes on the condensation ring her soda left on the table, “Mom used to tell me not to bother you. That you needed rest. But when I snuck into your room, you were never sleeping.

You were just lying there staring at the ceiling.”

I blinked back tears.

“You never bothered me,” I said.

“I know that now,” she said. “Back then, I thought there was something wrong with me for wanting to be around you so much.”

She lifted her gaze.

“There’s nothing wrong with you,” I told her. “Or with wanting to be where you feel seen.”

Her mouth trembled.

“Dad told me about the paperwork,” she said.

“About the signatures. About the medicine. About the five times thing.”

“The detective said you could have died,” she whispered.

“I didn’t,” I said gently.

“I know,” she said.

“But you could have. And I just…I’m glad you didn’t.”

She reached across the table and grabbed my hand.

Her fingers were ink-stained and warm.

For the first time since I’d woken up under a strange ceiling, I felt something that wasn’t fear or anger.

Gratitude.

After they left, the house settled around me like a quilt finally spread in the right direction.

It wasn’t perfect. There were still loose threads.

There would be hearings, maybe trials. There would be paperwork and statements and, inevitably, whispers at church and the grocery store.

But the center of it was no longer a question.

It was me.

I did my evening routine slowly, not because my body demanded it but because I wanted to feel every step.

I locked the doors. I checked the stove.

I set my heart pill and one half of a Zolpidem tablet beside a glass of water on the nightstand, more out of habit than necessity.

In the bathroom mirror, the woman looking back at me had more lines than the nurse who used to work double shifts, but the eyes were the same.

Tired.

Steady.

Not confused.

I washed my face and turned off the light.

In bed, the crack in the ceiling above me still split off like a crooked branch. The furnace hummed. Somewhere down the block, a dog barked once and fell quiet.

I thought about all the ways women lose themselves.

Not in one grand gesture.

In a series of tiny concessions.

You give up a shelf in your kitchen.

Then a drawer. Then control of your calendar. Then your pills.

Your mail. Your signature.

You call it helping.

You call it compromise.

You call it love.

Until one day you wake up under a ceiling that isn’t yours, with a tube in your throat and a detective at your bedside, and you realize the cost.

Old age doesn’t take our strength, I thought as my eyes finally grew heavy.

Silence does.

And I was done being silent.

If any piece of my story sounds like yours—if you’ve ever felt small in your own home, or doubted your memory because someone needed you to—know this much at least: you are not crazy, and you are not alone.

Tell someone. Write it down.

Say it out loud in whatever way feels safest.

Sometimes one voice, one honest sentence, is all it takes to remind another woman in the dark that there’s still a way back to herself.

It took longer than I expected for life to look ordinary again.

Not perfect. Not fixed. Just ordinary.

There were hearings to attend, statements to sign, phone calls from the detective that came at odd hours.

There were mornings when I’d be stirring oatmeal and the sight of steam rising from the pot would send me right back to that chipped white mug on my counter. I learned to ride those moments like waves passing through instead of storms that would drown me.

About three weeks after the night in the hospital, Detective Hail called to tell me the county prosecutor was filing formal charges.

“Attempted felonious assault,” he said. “Forgery.

Elder financial exploitation. They’re still finalizing the list.”

I sat at the kitchen table with my hand wrapped around my tea, watching the way the light hit the rim of the mug.

“What happens now?” I asked.

“There’ll be an arraignment first,” he said. “Then, unless her attorney negotiates some kind of plea, a series of pretrial hearings.

I’ll keep you updated on any dates you’re required to attend. For now, I wanted you to hear it from me, not from the news or a neighbor.”

“Thank you,” I said.

He hesitated, then added, “I know this is hard. But this is the part where the system does its work.

You’ve done yours.”

After we hung up, I sat there for a long time.

When you spend decades protecting other people from the worst nights of their lives, it’s a strange thing to realize one of yours is about to be read aloud in a courtroom.

The first time I saw Clara again was in that courtroom.

The Franklin County Courthouse downtown doesn’t look like much from the outside—just another gray box wedged between glass office buildings and parking garages. Inside, though, everything echoes. Every footstep.

Every whisper. Every quiet prayer.

David insisted on driving me. We rode in silence most of the way, the downtown skyline growing closer through the windshield, the freeway signs for I-70 and I-71 flashing past above us.

“Are you sure you want to go in?” he asked when he found a spot in a public lot and cut the engine.

His hands were still on the wheel.

“I’m sure,” I said. “If I could walk into an ICU at three in the morning to tell a stranger’s family their world just changed, I can sit in a room while someone reads out what happened to me.”

He swallowed and nodded.

Inside, the hallway outside the arraignment courtroom was crowded but hushed. People in suits, people in jeans, public defenders with briefcases, a bailiff with a clipboard.

The smell of old coffee and floor cleaner hung in the air.

Evelyn met us outside the door. She wore a dark suit this time, her curls pinned up more tightly than usual.

“Remember,” she said, touching my arm lightly, “you’re here to observe, not to perform. Let them do their jobs.”

I nodded.

We sat in the second row, close enough for me to see Clara when they brought her in, but not so close I could feel her breathing.

When the side door finally opened and the deputies led her in, I had to remind myself to inhale.

She looked smaller somehow in the county-issued jumpsuit, its orange fabric at odds with the polished woman who used to sweep into my kitchen with a designer tote and an air of control.

Her hair was pulled back without care this time, no sleek bun, just a ponytail. Her wrists were cuffed in front of her.

She didn’t look at me.

The prosecutor read the charges in a flat, practiced voice. Attempted felonious assault.

Two counts of forgery. One count of theft. One count of endangering an elderly person.

Her attorney entered a not-guilty plea on her behalf.

Not guilty.

The words were expected.

They still hit.

As the judge spoke about bond and conditions and the next court date, Clara’s gaze flicked briefly toward the gallery. Not to me. To David.

Something sharp twisted in my chest.

His face didn’t move.

Later, outside in the hallway, he clenched and unclenched his jaw so many times I thought his teeth might crack.

“I didn’t recognize her voice when she answered the charges,” he said quietly as we waited for Evelyn to finish speaking with the prosecutor.

“It sounded…hollow.”

“How do you hear someone after you’ve heard what they’re capable of?” I asked.

He didn’t answer.

That was a hinge neither of us could close.

The weeks that followed blurred into a strange rhythm of normal life and legal updates.

On Monday mornings, I’d do my grocery run at Kroger, picking up oatmeal and fresh fruit and the cheap bouquet of flowers I liked to split between a vase in the kitchen and a mason jar on the mantle. On Tuesdays, there might be a call from Evelyn about discovery, or from Hail about a hearing date, or from a victim advocate at the prosecutor’s office explaining what each step meant in plain English.

Some days, I’d sit at the table with my tea and read every word of the documents Evelyn sent, making notes in the margins with my old nurse’s pen. Other days, I’d set them aside and watch the snow melt on the maple tree out front, thinking about how many winters that tree had seen without once worrying who controlled the soil around it.

One Thursday, Lily came by after school with her sketchbook tucked under her arm.

“Dad’s at therapy,” she said, slipping off her sneakers and heading straight for the kitchen.

“He told me I could either go with him or come hang out with you. I picked you.”

“That’s a lot of pressure,” I said, smiling as I handed her a plate of apple slices.

She flopped onto the couch and pulled her knees up, balancing the sketchbook on them.

“What are you working on?” I asked.

“Nothing for class,” she said. “Just…stuff.”

She flipped the pages so I could see.

There were drawings of hands—old hands, young hands.

Hands knitting, hands gripping steering wheels, hands holding other hands. One page showed a mug, chipped on the rim, steam curling up from it in careful pencil lines.

“That one’s you,” she said softly.

“Because I’m cracked?” I teased.

“Because you’re more complicated than you look,” she said. “And because you’re the first person who ever told me it’s okay to put something down if it’s burning me.”

I looked at the mug on the page.

And I thought about how many years I’d held on to things that hurt.

“Can I ask you something?” Lily said after a while, her pencil hovering over a blank page.

“Anything.”

She chewed her lip.

“If this hadn’t happened—if she hadn’t gone too far, I mean—would you have ever told Dad how bad it felt? The way she treated you? The way she moved your stuff?”

The question settled between us.

Have you ever asked yourself that about your own life?

Whether you’d have spoken up without a disaster forcing your hand?

“No,” I said finally. “I probably would have just kept making excuses. For her.

For him. For myself.”

“Why?”

“Because I grew up in a generation where keeping the peace was considered a moral achievement,” I said. “Where a woman who stood up for herself was called difficult, but a woman who swallowed hurt was called strong.”

She frowned.

“That sounds backwards.”

“It is,” I said. “But when you’re inside it, it feels like the only way to keep a family from falling apart.”

She drew a line down the page.

“I don’t want to be like that,” she said quietly.

“You don’t have to be,” I replied. “You get to decide where your line is.”

She nodded, then went back to her drawing.

Some hinges open slowly.

One Sunday after church, my neighbor, Mrs.

Landon, caught up with me in the parking lot. The wind off the parking lot cut right through my coat, but she didn’t seem to feel it.

“How are you holding up, dear?” she asked, looping her arm through mine as we walked toward our cars.

“I’m…finding my balance,” I said.

“That’s a good way to put it.” She gave me a sideways look. “You know, a few of us ladies have started meeting on Wednesday afternoons at the community center.

Nothing formal. Just coffee and conversation. Some of the women are dealing with…situations similar to yours.

Husbands, sons, daughters, in-laws who think ‘helping’ means ‘controlling.’ You’d fit right in.”

A support group.

If you’d asked me a year ago whether I’d ever sit in a circle of folding chairs telling strangers about my daughter-in-law, I would’ve laughed you out of my house.

Now, the idea didn’t sound laughable at all.

It sounded like air.

“I’ll think about it,” I said.

“Don’t think too long,” she replied. “You’d be surprised how much easier it is to hold your boundaries when you’re not the only one in the room trying.”

Her words stayed with me all the way home.

That was another hinge.

On the first Wednesday I decided to go, the sky was a flat dull gray, the kind that made the whole world look like it needed fresh paint.

The community center on Parsons Avenue was a low brick building with a faded playground out back. Inside, the hallway smelled like coffee and crayons.

A hand-lettered sign taped to one of the doors read, “Circle—Women Supporting Women.”

I almost turned around.

Then I thought of Lily, drawing hands and mugs and telling me she didn’t want to grow up swallowing hurt.

I pushed the door open.

There were eight women sitting in a circle of mismatched chairs. Some had gray hair like mine. One looked as young as Lily’s math teacher.

There were cookies on a table, a pot of coffee, a box of tissues.

Mrs. Landon waved me over.

“This is Martha,” she announced. “She’s new, but she’s got a story.”

They all did, it turned out.

The woman beside me talked about a son who’d moved back home “temporarily” five years ago and never left, slowly taking over every room.

Another spoke about a brother who had “borrowed” her savings and stopped answering her calls.

When it was my turn, my hands shook a little in my lap.

“I’m Martha,” I said. “I’m seventy-one. I was a nurse for thirty years.

Three months ago, my daughter-in-law handed me a drink she said would help me sleep.”

I told them enough.

Not every detail. Not the legal codes or the exact dosages. Just the shape of it.

The mug. The pills. The paper she’d traced my name onto.

When I finished, the room was quiet.

Then the woman across from me—short hair, sharp cheekbones, a cardigan that had seen better days—said, “I’m so glad you lived.”

The others murmured in agreement.

It hit me then that I wasn’t the only one who knew what it was to nearly be erased by someone who claimed to love them.

“Thank you,” I said.

“Me too.”

If you’ve ever sat in a room like that, you know the way it changes you. It’s not about swapping horror stories. It’s about hearing your own doubts in someone else’s voice, and realizing you’re not crazy.

Walking out of the community center that day, the air felt a little less sharp against my lungs.

Somehow, sharing the weight had made it lighter.

Spring crept in slowly.

The snow retreated from the edges of the sidewalks.

The maple out front sprouted shy green buds. Kids on our street started leaving their winter coats unzipped again, ignoring their mothers calling after them.

Inside my house, small changes kept taking root.

David came over every Sunday afternoon now. No rushed dinners squeezed between work emails.

No tense holidays where Clara’s disapproval sat like a centerpiece on the table. Just slow afternoons where he helped me fix a loose cabinet door or change the battery in a smoke alarm I couldn’t reach.

Sometimes we talked about the case. Sometimes we didn’t.

One afternoon in April, he stood at the sink rinsing coffee mugs while I dried.

“I filed for legal separation,” he said without preamble.

I set the dish towel down.

“Are you sure?” I asked.

He stared at the suds sliding down the side of his mug.

“Mom,” he said, “a woman who could do what she did to you is not someone I can stay married to.

Even if a judge someday calls it something less than what it was, I know the truth now. I can’t unknow it.”

I watched his shoulders rise and fall.

“What about Lily?” I asked.

He nodded. “We’ve talked a lot about it in therapy.

She told me she feels safer knowing there’s a line. She said she’s tired of walking on eggshells. That’s not the life I want for her.”

He glanced at me.

“For years I told myself staying was the best way to protect her. Turns out leaving might be the only way.”

“Sometimes the hardest boundary is the one you draw around your whole life,” I said.

He huffed out a breath that was almost a laugh.

“Trust you to turn this into a lesson,” he said.

“Old nurses don’t retire,” I replied. “We just change the kinds of emergencies we show up for.”

We smiled at each other over the sink.

That little square of domestic normalcy felt like a miracle.

The preliminary hearing where I was scheduled to testify as a witness took place in May.

I wore my best navy dress and the cardigan Lily had given me for Christmas.

I pinned my hair up the way I used to for work, not because anyone expected me to, but because it made me feel like the version of myself who knew how to walk into hard rooms.

On the stand, the prosecutor walked me through that night step by step.

The kitchen. The mug. The taste.

The fall.

He asked about the pills. About the way the bottles had been rearranged. About the missing documents.

He asked me about my nursing background, about dosage awareness, about why I was so certain I hadn’t taken that much medication on my own.

Then Clara’s attorney took his turn.

He tried to be gentle.

“How old are you, Mrs.

Eldrich?” he asked, as if the answer might explain everything.

“Seventy-one,” I said.

“Do you ever forget where you put things?”

“Sometimes,” I replied. “The same way anyone does.”

He tilted his head. “Have you ever misplaced your glasses?

Your keys?”

“Of course,” I said. “But I don’t confuse my glasses with a stove burner. And I don’t confuse five times the prescribed dose of a sedative with one pill.”

A few people in the courtroom shifted.

He pressed.

“Is it possible,” he said slowly, “that you misunderstood what your daughter-in-law told you about the drink?”

“No,” I said.

“Is it possible that you misremembered whether you took additional medication that night?”

“No,” I repeated.

He frowned.

“You seem very sure.”

“I charted medications for three decades,” I said. “I logged every pill I gave a patient, every drop of IV medication. I know what goes into a body and what doesn’t.

I can forget where I set down a book and still remember how many milligrams are too many.”

A quiet murmur moved through the benches.

The judge tapped his gavel once.

“That will be enough,” he said.

When I stepped down from the stand, my legs felt like rubber. But my spine felt straight.

Outside afterward, Lily threw her arms around me.

“You were amazing,” she said. “That line about the glasses and the stove?

Iconic.”

“I wasn’t trying to be iconic,” I said.

She grinned. “That’s what makes it so good.”

Sometimes strength sounds like a woman answering the same question, firmly, without raising her voice.

Summer arrived in a rush.

The maple exploded into full green. Kids rode their bikes in circles around the cul-de-sac.

The ice cream truck’s tinny song drifted through the evenings.

The case crawled forward at the slow pace of the legal system. There were motions and continuances and negotiations I only half understood.

One afternoon, Evelyn sat at my table with a folder open between us.

“The prosecutor is leaning toward offering a plea,” she said. “If her attorney agrees, Clara would plead guilty to a reduced set of charges—likely forgery and attempted assault rather than the full list.

In exchange, she’d avoid a long trial. There would still be consequences. Probation at a minimum.

Possibly time in a correctional facility, depending on the judge.”

I traced the rim of my mug.

“Do they need my approval?” I asked.

“No,” she said. “But they want your input. Victims’ voices matter.

The advocate can arrange a meeting if you’d like to share how you feel.”

How did I feel?

I thought of Clara’s hands wrapping around the mug. Of her voice telling the detective I was confused. Of the extra clauses in the power of attorney.

I also thought of Lily.

Of the fact that whatever happened, Clara would still be Lily’s mother.

“I don’t need her in prison for the rest of her life,” I said slowly. “I just need her nowhere near my medications, my finances, or my front door.”

Evelyn nodded.

“We can request a no-contact order as part of sentencing,” she said. “And restrictions on her ability to serve in any fiduciary role for vulnerable adults.”

“That’s a lot of words,” I said.

She smiled.

“It’s lawyer-speak for: she won’t be able to do this to someone else as easily.”

“Then that’s what I want,” I said.

Justice, I was learning, rarely looks like television.

It looks like limits.

In August, on a day so hot the asphalt shimmered, Clara took the plea.

I didn’t go to that hearing.

David did.

He came by afterward, tie loosened, sweat dampening his collar.

“Six months in a correctional facility,” he said, sinking onto the couch. “Followed by three years’ probation. Mandatory counseling.

A no-contact order with you. Restrictions on handling anyone’s finances but her own.”

He stared at the floor.

“She cried,” he said. “Said everyone turned against her.

Said she never meant to hurt you that badly. That she was just overwhelmed.”

I sat in my chair across from him, the one that had molded to my shape over decades.

“What did you say?” I asked.

“Nothing,” he said. “There wasn’t anything left to say.”

For a long moment, we listened to the hum of the air conditioner and the distant shrieks of children in the sprinkler down the block.

“Do you feel guilty?” I asked.

He considered.

“I feel sad,” he said.

“For Lily. For the years I didn’t see what was right in front of me. For the part of Clara that might have been different once.”

“But I don’t feel guilty for choosing you,” he added.

“Not anymore.”

I let that sink in.

If you’ve ever had to choose between keeping the peace and protecting yourself, you know how heavy that kind of sentence is.

Sometimes the most radical thing a person can say is, I choose me.

Life didn’t magically become light and easy after that.

There were still days when I’d walk past the maple and remember the way Clara had stood behind it, watching. There were nights when I’d wake up at two in the morning, heart racing, convinced I heard footsteps in the hall, only to realize it was the furnace kicking on.

There were awkward moments at church with people who didn’t know the whole story but had heard enough to make them curious.

But the sharpest edges softened.

Lily started high school that fall. On her first day, she insisted on stopping by my house so I could see her outfit—jeans, a denim jacket, a T-shirt she’d designed herself with a line drawing of a mug and the words “Too Strong” printed underneath.

“Do you like it?” she asked, spinning once.

“I love it,” I said.

“It’s very you.”

“It’s very you,” she corrected. “You’re the one who survived the drink.”

I laughed.

“If anyone asks,” I said, “tell them it’s about coffee.”

She grinned. “That’ll be our secret.”

She hugged me hard at the door.

“Grandma?” she said.

“Yes?”

“Thanks for not dying.”

We both laughed.

Then she looked serious.

“And thanks for not pretending it was nothing,” she added.

“If you’d kept pretending, I think I would’ve learned to do the same.”

Her words sat with me long after she left.

I had spent so many years worrying about what my silence taught my son.

I hadn’t considered what my voice might be teaching my granddaughter.

On a cool Saturday in October, the women from the community center invited me to share my story at a larger gathering—part of an elder law awareness event downtown.

“Just a few minutes,” the organizer said over the phone. “Nothing fancy. We’ll have attorneys and social workers talking, but people remember stories more than statutes.”

I hesitated.

Public speaking was never my favorite part of nursing.

I preferred one-on-one conversations at two in the morning in dim rooms.

But I thought about all the women who never made it to a hospital bed in time. About the ones who’d been written off as confused when they were really being slowly erased.

“Okay,” I said. “I’ll do it.”

The event took place in the basement of a downtown library branch.

There were fold-out chairs, a podium that wobbled a little, a table with coffee and cookies in the back.

When it was my turn, my hands shook as I walked up.

Then I saw Lily in the second row, sketchbook in her lap, drawing my profile.

I took a breath.

“I’m Martha,” I began. “I’m seventy-one. I spent three decades as a nurse in this city before I retired.

I thought I knew what danger looked like. I thought it wore sirens and car crashes and sudden heart attacks.”

I told them about the mug.

About five times the dose.

About the paper with my traced signature.

I told them about the way Clara had moved into my drawers and my documents and my decisions long before she ever touched my pills.

And I told them about the day I finally said no.

“When you’re my age,” I said, “people expect you to be grateful for whatever help they offer. They expect you to say yes when they rearrange your life for you.

They expect you to keep the peace, even if it kills you.”

I scanned the room.

“Have you ever felt that?” I asked. “Like your gratitude was being used as a leash?”

A few heads nodded.

“Here’s what I’ve learned,” I said. “You’re allowed to ask questions.

You’re allowed to see the label on the bottle. You’re allowed to say, ‘No, that’s my signature, and you don’t get to use it without me.’”

I swallowed.

“You’re allowed to choose yourself and still be a good mother. A good wife.

A good grandmother. A good person.”

Afterward, an older man in a veterans cap shuffled up to me.

“My daughter’s been ‘helping’ me with my bank account,” he said, making quotation marks in the air. “I think I’m gonna ask the lawyer over there a few questions.”

“Good,” I said.

Sometimes the bravest thing we do is let our worst night become someone else’s warning light.

Now, months later, if you were to walk past my house on Maple Glen Drive, you’d probably think nothing extraordinary had ever happened there.

The shutters are still blue.

The maple still drops leaves in wild red and gold drifts. The porch still has two chairs, one for me and one for whatever grandchild or neighbor feels like sitting a while.

Inside, the kitchen drawers are organized the way I like them.

My medications sit in a clear plastic box on the counter, labels facing out, exactly where I can see them.

The chipped white mug lives on the second shelf now. I still use it.

Sometimes I think about throwing it away.

But then I remember the number five.

Five times the dose.

Five signatures traced.

Five doors I shut: my mailbox, my medicine cabinet, my bank account, my front door, my voice.

I’d rather keep the mug and remember why I count.

In the evenings, when the house is quiet and the furnace hums and the maple’s branches scratch lightly at the window, I sit in my armchair with a blanket over my knees and this notebook in my lap.

I write.

Some of it is for me.

Some of it, I know now, is for whoever might someday read it and see themselves between the lines.

If you’ve made it this far with me, maybe that’s you.

Maybe you’ve stood in your own kitchen, holding a metaphorical mug someone else mixed for you, telling yourself it would be easier to drink than to ask what’s in it.

Maybe you’ve let someone rearrange your drawers, your schedule, your stories, because saying no felt too dangerous.

Maybe you’ve wondered, quietly and guiltily, what would happen if you finally said, “That’s enough.

This is my life.”

If any of that sounds familiar, I’d ask you this: Which moment in my story landed hardest for you?

Was it the beeping monitor under a strange ceiling? The missing bottle on the nightstand? The forged signature buried in a file box?

The day I told Clara she no longer had a key to my front door? Or the afternoon I watched my granddaughter draw a mug and write “Too Strong” underneath it?

And one more question, the one I wish someone had asked me years ago: What was the first boundary you ever drew with your own family—and what boundary do you know, deep down, you still need to draw?

You don’t have to answer me out loud.

You don’t have to write it anywhere but in your own heart.

But if an old nurse from Columbus, Ohio, can wake up under the wrong ceiling, almost lose everything, and still find her way back to herself, I promise you this much.

You are allowed to choose a different ending.

And it can start with one small, steady word.