The concrete was cracked. The railing was rusted.

Nobody had crossed it in years. Camille knew that.

That was exactly why she had chosen it.

For one second, her hands tensed, fingers tightening around the girl’s wrists. Rosalie screamed, believing that was the moment she would be pulled back to safety. But it was only a cruel illusion.

Camille’s face hardened.

“Everything I had is gone because of you,” she said through clenched teeth. “My peace.

My joy. My dreams of being a mother.”

And then, without a shout, without another warning, she let go.

Rosalie’s shriek tore through the cold night air.

It was a short, piercing sound that disappeared between the wind and the echo off the metal and concrete. Her small body dropped, spinning once before it hit the water. The impact was violent.

The surface opened and closed again almost instantly, as if nothing had happened.

Silence. Camille stood frozen, her heart hammering against her ribs.

She stared down at the river. The dark current continued its course, indifferent.

For a moment, bubbles rose to the surface, then vanished one by one.

No more movement. She breathed in once, twice. “It’s done,” she murmured.

“It’s over.”

She turned slowly, walked back to the car parked at the end of the bridge, and slid behind the wheel.

Her hands shook, but her face remained rigid. She started the engine and drove away from the bridge without looking back.

What Camille didn’t know was that the river hadn’t taken the girl’s life. It had only taken her memory.

And what fate hadn’t revealed yet was that somewhere downstream, a twenty-year-old woman named Iris Callaway—a woman who had grown up with nothing, who had survived foster homes and hardship and every kind of abandonment the system could throw at a child in America—was about to pull a dying girl from the dark water with her bare hands.

That single act would one day bring Iris face to face with the most dangerous man in Chicago. Not as his enemy, but as the woman he would learn he couldn’t live without. At the same time, only a few miles downstream from that same bridge near the quiet river town of Grafton, Illinois, an old, faded silver-gray pickup truck crept along a dirt road that hugged the river’s edge.

The left headlight flickered as if it were about to die.

The right one had been dead since the week before. Behind the wheel sat Iris Callaway, twenty years old, thin, her hair tied up high, revealing a slender neck marked with mosquito bites.

Dark circles sat under her eyes from lack of sleep. Her hands were rough from doing far too much work for someone her age.

Everything Iris owned in this world fit inside a canvas backpack on the passenger seat: two changes of clothes, a small box of adhesive bandages, forty-seven dollars in cash, and a small, faded photograph of her at three years old, sitting in the lap of a woman whose face she could no longer clearly remember.

That was her mother, or at least the woman the group home had told her was her mother. Iris had been orphaned at the age of three after a house fire in the middle of a winter night on the West Side of Chicago. Her parents hadn’t made it out.

She had survived because a neighbor smashed the bedroom window and lifted her through the black smoke to the frozen yard outside.

From that moment on, Iris entered the Illinois foster care system and never once exited it through any door that led toward light. Seven foster families in fourteen years.

The first sent her back after six months because they said she cried too much at night. The second kept her for a year and then chose to take in a newborn instead because they thought it would be easier.

The third was where she learned that adults could smile during the day and still hurt children at night.

The foster father had a belt he used when he was drunk. The foster mother pretended she couldn’t hear. The fifth was the one Iris never wanted to talk about.

The house where a middle-aged man crossed boundaries no adult should ever cross with a thirteen-year-old child.

When she finally spoke up, no one believed her because he was a church deacon and she was just a foster kid with no one to stand beside her. Iris aged out of the system at seventeen with exactly one black plastic trash bag of clothes and not a single adult looking back.

She slept in shelters, then in her car, then on benches at the Greyhound station. She worked whatever jobs paid cash the same day: washing dishes at a Chinese restaurant, scrubbing motel floors, waitressing at small bars, anything that brought money fast.

At nineteen, she met a man named Wade.

He told her he loved her. It was the first time anyone had ever said that to Iris, so she believed him. Three months later, Wade hit her for the first time.

Six months after that, he beat her in a parking lot behind a bar in the middle of the night so badly that two of her ribs were broken and her left cheekbone was fractured.

Iris spent two months in a charity hospital in Chicago. No one came to see her.

No one called. On the day she was discharged, she looked at herself in the mirror, at the faint scar along her cheekbone, and told herself, “You’re not going to die here.

Not like this.

Not because of a man. Not because of anyone.”

She bought the old pickup truck with all the money she had saved and drove south out of Illinois with no real plan and no destination—only the need to leave Chicago, the city of her losses, behind. That night, as the truck crawled along the riverbank, the headlight flickered and then went completely dark.

Iris pulled over, muttered under her breath, opened the door, and stepped out to check it.

Cold air cut into her skin. The river roared in the darkness beside her.

She was bent over the front of the truck when she heard something strange. Not the sound of water hitting rock.

Not the whistle of wind.

Something weaker, thinner, like a small animal scratching at the surface of the water. Iris straightened and listened. The sound came again, this time followed by a choking cough.

She ran to the riverbank.

Thin moonlight spread across the black water, and Iris saw it: a tiny shape drifting into the shallows near the shore, face down, hair floating like weeds, both arms limp. Iris didn’t think.

She ran straight into the water. The river was so cold it nearly stole her breath in the first second.

The water rose to her chest.

Her feet slipped on mossy stones, but she kept going. She grabbed the child’s arm, pulled the small body toward her, and rolled it over. A small bluish face.

Lips pale.

Eyes closed. Not breathing.

Iris dragged the child onto the bank, laid the limp body on the wet grass, dropped to her knees, and began compressions. “One, two, three, four, five,” she counted under her breath, then breathed into the child’s mouth.

Again.

“One, two, three, four, five.”

No response. She kept pressing, tears spilling down her cheeks before she even realized she was crying, her voice barely audible as she whispered like a prayer even though she hadn’t believed in God since that fifth foster home. “Breathe,” she told the child.

“Breathe.

I am not letting you go. Do you hear me?

I won’t let you go.”

Then the child coughed. Water poured from her mouth and nose.

The tiny body convulsed, shuddered, and then a weak cry slipped out, so soft the wind almost carried it away.

But Iris heard it. She heard it clearly. She lifted the child and pulled her close, pressing the trembling little body against her chest, wrapping both shaking arms around her and crying—not because of sorrow, but because for the first time in twenty years of living, Iris Callaway was holding on to someone who wasn’t slipping through her hands.

“I’ve got you,” she whispered into the child’s ear, shivering in her arms.

“I’m not letting go. I swear I’m not letting go.”

A few hours before Iris plunged into the black water to pull a child onto the bank, that same morning at a Gold Coast mansion north of downtown Chicago began like every other morning in Killian Voss’s house.

October sunlight streamed through wide glass windows, spilling across the marble kitchen floor where a twenty-seven-year-old man sat flat on the ground, legs stretched out, his back against the cabinets, while a six-year-old girl stood behind him with a serious frown, her tiny hands busy tying a pink ribbon into his dark hair. Killian Voss—the man who twelve hours earlier had ordered his right-hand man, Declan Frost, to dismantle a money operation that had dared to encroach on his territory on the South Side.

The man whose name people in Chicago whispered with the same wary respect they reserved for storms and for God.

That man sat perfectly still on his own kitchen floor so his six-year-old daughter could tie a bow in his hair without him moving an inch. “Don’t move, Daddy,” Rosalie said, her voice stern in the way only children could be without frightening anyone. “I’m not done yet.”

“Are you done, Rosie?” he asked, amusement hidden behind his patience.

“Not yet.

If you move, I start over.”

Killian smiled. The kind of smile no one outside this house had ever seen.

The kind of smile no one in Chicago believed he was capable of. This was the only part of his day when he was an ordinary man.

Every morning he woke at five, before Rosalie stirred.

He put on a robe and went down to the kitchen to make pancakes because that was the only breakfast she would eat. He sliced bananas into star shapes and scattered them on top because she said stars tasted better than circles. He poured orange juice into the purple plastic cup Rosalie called her princess cup.

When she woke up, she ran down the stairs with her hair in a wild tangle, eyes still heavy with sleep, and her first words were always, “Daddy, how are we braiding my hair today?”

Some mornings it was twin braids.

Some mornings a ponytail. Some mornings Rosalie wanted to braid her father’s hair first before her own.

Killian let her do whatever she wanted. He hadn’t been good at braiding in the beginning.

In truth, he was so bad that Rosalie cried from the tugging.

But he watched more than fifty tutorial videos on YouTube late at night after the house went quiet. Now he could do a French braid faster than any mother at Lincoln Park Preschool. No one knew that.

Declan didn’t know.

The men didn’t know. The outside world saw only Killian Voss in a black suit, with cold eyes and a voice that rarely rose more than a single note.

They didn’t see him lying face down on the living room rug, pretending to be a monster while Rosalie climbed onto his back, laughing. They didn’t see him reading Goodnight Moon every night in a low, steady voice until she fell asleep on his arm, then lying still for another twenty minutes because he was afraid to wake her.

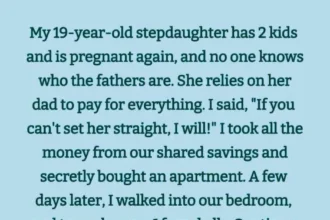

Rosalie’s biological mother was named Margot.

She had died on the operating table. The doctors had said they could only save one. Margot had decided before she went into surgery.

“If you have to choose, save the baby,” she’d said.

Killian never spoke of Margot to anyone. He kept her photograph locked in a drawer in his study.

Not because he had forgotten her, but because every time he saw her face, he saw the delivery room, the white lights, the monitor flattening into a single straight line. He didn’t want Rosalie growing up in a house where her father collapsed every time he passed a picture frame.

He buried that pain as deep as it would go and made up for it by loving Rosalie twice as much as Margot had never had the chance to.

“Daddy, are you coming home early today?” Rosalie asked as Killian stood up, the pink bow still dangling in his hair. “I’ll try, my light,” he said, bending to kiss her forehead. He breathed in her scent—children’s shampoo, milk, pancakes—as if he were trying to memorize it with every cell in his lungs.

Then he put on his suit, stepped outside, climbed into the black Escalade waiting for him, and headed toward the city.

He didn’t know it was the last time he would ever see that pink bow. The front door closed.

The mansion fell silent. Camille Ashworth stood on the second floor, looking through the window as Killian’s car disappeared at the end of the long American driveway.

She didn’t move until it vanished around the bend.

Then she turned and faced the mirror. The woman staring back at her was thirty-two, born into high society, daughter of a former Illinois state senator, educated in private schools, dressed in designer clothes, trained to smile at the proper moments and say the right things at every fundraiser and gala. But that morning, the face in the mirror looked ten years older.

Two years earlier, when Camille had married Killian, she believed she had stepped into the life she deserved: power, money, a man the entire city of Chicago feared.

She would give him a son, an heir, and her place in his empire would be unshakable. But six months after the wedding, a doctor at Northwestern Memorial Hospital in Chicago told her that her uterus could not safely carry a child.

Not now. Not ever.

Camille cried for three days in the bathroom without letting Killian see.

She went to another hospital, then another, then a private clinic in New York, then a specialist in Los Angeles. They all said the same thing. From that moment on, every time Camille looked at Rosalie, she didn’t see a child.

She saw proof—proof that a woman who was dead could still give Killian something she, the woman alive and lying beside him every night, never could.

That pain didn’t disappear. It only changed shape.

The first month, it was sorrow. The third month, anger.

The sixth, a sharp jealousy.

By the second year, it had become something nameless, something thick and dark living in her chest, breathing with her every day. That morning, Camille heard Rosalie singing in the yard below. The child was watering flower pots she had planted herself, singing as she worked in the clear, bright voice of a six-year-old girl in an American garden.

Every note struck Camille’s chest like a slap.

She closed her eyes. She had been thinking about this for weeks.

She had rejected it, prayed against it, cried over it, searched for reasons not to do it. But this morning, standing in front of the mirror, listening to the child’s voice drift up from below, Camille didn’t resist anymore.

It was no longer just a thought.

It had become a decision. She went downstairs, stepped into the yard, and called Rosalie in the gentlest voice she could fake. “Come here, sweetheart.

Go put on something pretty.

Mommy’s taking you out.”

Rosalie’s eyes lit up. “We’re going out, Mommy?

Really?”

“Yes,” Camille said, smoothing the child’s hair. Her hand didn’t tremble.

“Just a little drive.

You and me.”

Rosalie smiled. In her small heart, hope bloomed. Maybe today Mommy really did love her.

Maybe her nightly prayers had been heard.

She ran inside to change, not knowing it was the last time she would leave that house on her own two feet. Camille started the engine.

The road ahead led toward the outskirts, the places the city forgot. She drove for five long hours, watching the Chicago skyline disappear in the rearview mirror as she headed toward the desolate riverbanks of southern Illinois, and Rosalie sat in the back seat, legs swinging, eyes turned toward the window, unaware that every mile carried her farther from everything she had ever called home in the United States.

Killian Voss arrived back at the Gold Coast mansion at eight that evening, two hours later than his morning promise.

He carried a bag of fruit from a farmers market because Rosalie liked green grapes and he always bought green grapes when he came home late—a wordless apology he never said out loud. He pushed the door open and stepped inside. The living room lights were off.

The kitchen was dark.

There was no smell of dinner. No sound of the cartoon Rosalie usually watched before bedtime.

No small feet running out to greet him the way they did every night. “Rosie?” he called, setting the bag of fruit on the kitchen counter.

“Rosie, Daddy’s home.”

Still nothing.

Killian went upstairs. Rosalie’s bedroom door was open. The light was off.

The bed was empty.

Her stuffed bear lay neatly on the pillow. The small flower pot on the windowsill, which she had watered that morning, still had damp soil.

He checked the bathroom, the playroom, the third floor, the backyard, the shed, the garage. Rosalie was nowhere.

He called Camille.

The phone rang five times before she picked up. Camille’s voice on the other end was shaking and breathless, exactly like someone in panic—or exactly like someone who knew how to perform panic. “Killian, I don’t know what happened,” Camille said, her voice breaking.

“I went out to buy a few things for about an hour.

When I came back, Rosalie wasn’t in the house. I looked everywhere.

I asked the neighbors if anyone had seen her. I’m sorry.

I’m so sorry.

I don’t know—”

Killian said nothing for three seconds. They were the longest three seconds of Camille Ashworth’s life. Then he spoke one sentence, his voice low and flat, colder than any shout.

“Come home.

Now.”

He ended the call and dialed Declan Frost. Declan listened and said only two words.

“I understand.”

Fifteen minutes later, the machine Killian Voss had spent nearly a decade building began to move under a single order. Find Rosalie.

Dozens of men spread out across the Gold Coast, Lincoln Park, Old Town, all the way down to Pilsen and Back of the Yards.

Every bar Killian controlled, every warehouse, every dock, every alley was searched. Declan called in every connection inside the Chicago Police Department—not through official channels, but through officers the organization had cultivated for years. Detectives and sergeants who took envelopes each month and looked the other way when needed.

Tonight, no one was allowed to look away.

The missing child report was filed at 9:45 that night. Six-year-old girl: Rosalie Voss.

Missing from her residence. Last seen around 8:30 that morning, before her stepmother left for errands.

County officers arrived to take statements.

Camille sat on the sofa, eyes red, hands wrapped around a glass of water, reciting the story she had rehearsed. She had gone out. When she returned, the child was gone.

The back door was ajar.

Maybe Rosalie had wandered out on her own. Camille cried at the right moments, hesitated at the right places, and not a single detective in the room suspected her.

Killian stood in the corner, not sitting, not speaking, only listening. His eyes were on Camille, without expression.

He didn’t suspect her.

Not yet. Not tonight. His mind held only one question:

Where is my daughter?

When the police left, when Declan went outside to coordinate searches, when Camille went upstairs and closed her door, Killian entered Rosalie’s room alone.

He turned on the light. Everything was untouched.

The small bed with butterfly sheets. The stuffed bear named Mr.

Honey that Rosalie slept with every night.

The drawing she had made of her father in crayon and taped to the wall: a tall stick figure with black hair next to a tiny stick figure with curly hair. Underneath, in uneven childish letters: “Me and Daddy.”

Her fuzzy bunny slippers lay beside the bed, neatly aligned, as if she still planned to come back and slip them on before sleeping. Killian picked up the stuffed bear.

It still smelled like her—shampoo, milk, a hint of grass from the last time she played in the yard.

He stood there in the middle of the room, the bear in his hands, and didn’t move. Outside, dozens of people were tearing the city apart under his orders.

His phone vibrated constantly. Declan called every fifteen minutes with updates.

Police were reviewing security cameras.

K-9 units were deployed around the neighborhood. But in this room, Killian wasn’t a boss. He wasn’t the man all of Chicago feared.

He was just a father holding his daughter’s stuffed bear and not knowing where his child was.

His knees hit the floor before he realized he was kneeling. He didn’t kneel because he chose to.

His legs simply could no longer hold him. Killian Voss had once knelt at his father’s grave when he took over the empire at twenty-three—not from grief, but from oath.

Tonight, he knelt on the floor of his daughter’s bedroom because of something no one in his empire had ever prepared him for: helplessness.

Power couldn’t find her. Money couldn’t find her. The fear he had planted across this city for years couldn’t bring her back.

For the first time in his life, Killian Voss understood that there were things he couldn’t command, couldn’t buy, couldn’t threaten, and couldn’t control.

He pulled the stuffed bear to his chest, closed his eyes, and whispered into the empty air, “Daddy will find you. I swear, Daddy will find you.”

During the first week, Killian didn’t sleep.

He turned the study in the mansion into a command center. A map of Chicago spread across the table, searched areas marked in red ink.

His phone stayed on speaker twenty-four hours a day, waiting for any call from Declan or the police.

He hired three of the largest private investigation firms in Illinois to work in parallel. He posted a reward of five hundred thousand dollars for any information leading to Rosalie and had people plaster her photo on every light pole, every gas station, every community bulletin board from Chicago all the way down toward Springfield. In the second week, surveillance results from around the Gold Coast started coming in, and that was when everything began to go wrong.

Footage from Astor Street showed Camille’s car leaving the house at 8:30 in the morning.

But when detectives requested footage along the route she might have taken, three of the five cameras were suddenly reported broken. One camera’s data had been “overwritten” due to a system error.

The final camera on the road leading toward the southern suburbs was blank, as if someone had wiped it clean before anyone had time to check it. Killian didn’t know that the person behind this invisible eraser was Neil Ashworth, Camille’s father.

Neil Ashworth was sixty years old, a former three-term Illinois state senator, a man whose name was etched on honor boards in Springfield and in the mental debt ledgers of dozens of officials from county to state level.

Neil hadn’t known what his daughter was going to do before she did it. But when Camille called him at ten that night, sobbing and confessing everything, Neil didn’t call the police. He didn’t shout.

He didn’t tell his daughter to turn herself in.

He was silent for ten seconds. Then he said, “Don’t tell anyone else.

Let me handle it.”

To Neil, this wasn’t simply a moral issue. It was a matter of survival—political, social, and personal.

If the truth came out, Camille would go to prison for attempting to kill a child.

The Ashworth family name would be dragged through a national scandal. Any remaining influence Neil held on boards, councils, and committees would vanish overnight. And worse, Killian Voss would not wait for a courtroom verdict.

Neil knew exactly who Killian was.

Neil acted that same night. He called the lieutenant overseeing the district police, a man Neil had helped promote five years earlier with the right phone call.

He called a Cook County judge whose campaign he had quietly supported. He called the director of the traffic camera department whose son had received a scholarship to Northwestern with Neil’s recommendation.

Call by call, old favors were collected.

Strings were pulled. Camera evidence disappeared. The detective assigned to the case was quietly transferred to another division and replaced by someone less experienced and easier to nudge.

Reports to the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children required complete documentation from local police to enter the federal database.

Yet the files submitted on Rosalie were always missing something—missing photos, missing detailed descriptions, missing key identifying notes—preventing effective federal cross-referencing. Killian never saw the invisible wall.

He saw only the result. No leads.

No progress.

No answers. All three private investigation firms reported the same thing: every trail ended abruptly, as if someone had deliberately severed each connection. By the third month, Killian began searching on his own.

He drove to every hospital, every morgue, every orphanage within two hundred miles of Chicago.

He carried Rosalie’s photo, asked every person, looked into every child’s face, and every time the answer was no, he drove to the next place. Declan went with him on every trip, saying nothing, taking the wheel whenever Killian was too exhausted to drive.

The first year passed. Then the second.

In the third year, Chicago police officially closed the case.

“Missing, presumed deceased. No new evidence.”

Declan brought the report to Killian. Killian read it, folded the paper, placed it in a drawer, and said, “She isn’t gone.”

When Declan said the police wouldn’t reopen the file, Killian replied, “Then we’ll find her ourselves.”

And he kept searching.

The fourth year.

The fifth. The sixth.

Hundreds of thousands of dollars poured out every year. No results.

Throughout that time, Killian watched Camille.

He didn’t accuse her because he had no proof. But something felt wrong. Something he sensed with the instincts of a man who had spent his life among liars.

Camille didn’t look for Rosalie.

She cried when people were watching. She asked about progress just often enough that silence would have seemed strange.

But she never drove out to search on her own. Never called detectives directly.

Never stayed up all night studying maps the way he did.

Killian never said it out loud, but he began keeping her close—not out of affection, but because he wanted to see her every day. He wanted to watch her eyes whenever someone mentioned Rosalie. He wanted to wait for the moment she made a mistake.

He didn’t throw her out.

He didn’t divorce her. He kept her in the Gold Coast mansion like a piece on a board whose next move he hadn’t yet decided.

Camille lived in that house as if inside a glass cage. From the outside, it looked like the privileged life of a powerful American businessman’s wife.

Inside, she knew Killian was watching her.

She knew he was waiting. And that fear, combined with a conscience she thought had died but had only been sleeping, began to consume her from the inside, slowly, day by day, like a disease. In the third year after Rosalie’s disappearance, Camille developed an autoimmune illness.

Lupus attacked her joints, her skin, her kidneys.

Doctors said prolonged stress was the trigger. Camille knew it wasn’t just stress.

It was guilt. The thing she thought she had killed on the bridge had only been pushed down.

Now it was awake, living inside her, wearing her down.

Her hair fell out in clumps. Her skin broke into rashes whenever the Chicago cold came. Her hands swelled so badly some mornings she couldn’t hold a glass of water.

But she didn’t dare tell anyone.

She didn’t dare call her father. Every call could be overheard.

And Killian didn’t miss details. So she sat in the mansion staring out the windows, rotting slowly in silence, while on the highest floor of a downtown high-rise, her husband sat on the floor of an empty child’s bedroom and spoke to a memory.

While Killian scoured Chicago, more than three hundred miles to the south, Iris Callaway was driving her old pickup truck through the night along rural roads with an unconscious child wrapped in her only jacket on the back seat.

The child was breathing, but the breaths were weak and uneven, sometimes followed by a faint moan before falling silent again. Iris didn’t know where to take her. She had no health insurance, no phone, and no idea where the nearest clinic was.

She drove toward light.

Just before four in the morning, she saw a small roadside sign that read:

GRAFTON COMMUNITY HEALTH CLINIC

She turned in. The Grafton rural clinic was a single-story white building with three exam rooms, a small emergency area, and one doctor on duty at night.

Iris ran inside carrying the child, still soaked in river water, hair plastered to her face, shaking so hard she could barely form a sentence. She told the doctor she had pulled the girl from the river, that she didn’t know who the child was, and begged him to help her.

The exam showed a head injury—a large swelling at the back of the skull, likely from impact during the fall into the water or from striking rocks beneath the surface.

The child was hypothermic. There was some water in her lungs, but not much, thanks to Iris’s desperate first aid. The doctor asked if Iris knew the child’s name.

She didn’t.

If there were any documents on her. No.

Was Iris family? “No,” Iris said.

“I just found her in the river.”

The clinic called local law enforcement.

A small-town sheriff arrived in the morning, took notes, photographed the child, and sent a report up the chain. But Grafton was a town of fewer than seven hundred people at the junction of the Mississippi River and the Illinois River right there in the American heartland. The sheriff also handled patrol duty, and communication with federal databases passed through more layers of paperwork than a place that small could move quickly.

The report was sent.

But back in Chicago, Neil Ashworth’s hands were already at work, blocking any information matching Rosalie Voss before it could reach the right eyes. The child stayed in the clinic for three days.

On the second day, she opened her eyes. The doctor asked her name.

The child looked at him with an empty gaze and shook her head.

“Where are you from?”

She shook her head again. “Where are your parents?”

No answer. The diagnosis was complete amnesia caused by head trauma—possibly reversible over time, possibly permanent.

The child didn’t remember her name.

She didn’t remember faces. She didn’t remember anything before falling into the water.

Her world started the moment she opened her eyes in that small hospital bed in Grafton, Illinois. Iris didn’t leave.

She had no money to pay the bill, nowhere to go, and only one reason to stay.

She couldn’t leave the child alone. She slept on a plastic chair beside the bed. She ate crackers and bread from the vending machine with what little cash she had left.

Whenever the child woke in the night in panic, unable to remember who she was or where she was, Iris held her hand and said, “It’s okay.

I’m here. You’re not alone.”

Two weeks passed.

No one came to claim the child. No calls from family.

No missing child photos that matched in the system Grafton police could access.

No inquiries. The girl existed as if she belonged to no one in the world. In the second week, Harold and June Whitfield came to the clinic.

Harold was seventy-two, had spent his life fishing and repairing boats along the Mississippi.

His back was bent, his hands calloused, his eyes kind. June was sixty-eight, a former elementary school teacher in town before retiring—silver hair pinned up, known for bringing baked goods to clinic patients every weekend.

They heard from a nurse about the unclaimed child and the young woman who had slept on a plastic chair for two weeks without leaving. June stood outside the doorway and looked into the room.

She saw Iris sitting by the bed, reading to the child from an old magazine picked up in the waiting room.

The girl listened with wide eyes, silent, one small hand wrapped around Iris’s finger. June turned to Harold and whispered that they couldn’t leave these two alone. Harold nodded.

They went in, spoke with Iris, spoke with the doctor, and completed temporary guardianship paperwork with the local child services office.

In a small American town, the process wasn’t as complicated as in a big city. With the endorsement of the clinic doctor and the sheriff, Harold and June took the child home.

On the first day at the Whitfield house, the girl barely spoke. She sat on the bed, looking around the unfamiliar small room, fear filling her eyes.

That afternoon, June opened the window for fresh air, and a flock of sparrows landed on the tree branch just outside the sill.

The child stood up for the first time without help, walked to the window, and watched. Her eyes lit up just a little—but enough for June to notice. It was the first light on the child’s face since she had opened her eyes at the clinic.

June called Harold to look.

“She likes birds,” June murmured. Harold watched the girl standing by the window, fingers touching the glass, mouth slightly open at the sound of birdsong, and said, “Then we’ll call her Birdie.”

The name stuck.

From that day on, the child with no name, no past, and no memory had a new name and a small home by the Mississippi River. Iris stayed three more days to make sure Birdie was settled.

She helped June tidy the room, helped Harold repair an old bed to fit the child, and each night she sat beside Birdie until she fell asleep.

On the morning Iris finally had to leave, she sat by Birdie’s bed. Birdie looked at her with the eyes Iris had watched for two weeks—eyes that remembered nothing, yet trusted completely. “Will you come back after you go?” Birdie asked.

Iris held her hand tightly.

“I promise,” she said. Then she got into her truck and drove away, watching in the rearview mirror as the small house and June standing on the porch holding Birdie grew smaller and smaller until they disappeared around the bend.

Iris wiped her tears with the back of her hand and kept driving forward, not knowing where she was going, only knowing that for the first time in her life, she had made a promise she was determined to keep. Eight years passed.

Killian Voss was thirty-five now, and anyone who had known him at twenty-seven wouldn’t have recognized the man standing on the highest floor of Voss Tower at three in the morning, looking out over the Chicago skyline.

He hadn’t aged much physically—still tall, still solid, still wrapped in a perfectly tailored black suit. But something in his eyes had gone dark the night he knelt on his daughter’s bedroom floor, and it had never come back. His empire, by contrast, shone brighter than ever, at least to the outside world.

Voss Holdings was now the third-largest real estate and hospitality group in the southern half of the city, owning four luxury hotels along Michigan Avenue, two restaurants listed in the Michelin Guide, and stakes in a chain of legal casinos in Indiana that Killian controlled indirectly through clean names—straw owners paid generously to sign papers and ask no questions.

On the surface, Killian was a powerful American businessman, invited to charity galas, shaking hands with the mayor, posing for photos with city council members. Beneath that surface, he was still the darkness whispered about in every alley on the South Side.

The underground network ran parallel to the legitimate empire: shipping routes along the Mississippi, money washed through restaurants and laundromats, unlicensed casinos hidden in basements under buildings that rented out office space above ground. Everything was run by Declan Frost with the precision of a Swiss watch and protected by the absolute loyalty of men who understood that betraying Killian Voss was not a choice.

It was a sentence.

Killian was far more ruthless than he had been eight years earlier. Before Rosalie vanished, he had been cold but restrained, still able to tell the difference between necessity and cruelty. Now that line no longer existed.

A courier delivered late by two days, and Killian didn’t ask why.

He gave the order and Declan handled it. The man disappeared from Chicago overnight.

A business partner tried to skim twenty percent of the profits. Killian invited him into his office, sat across from him, spoke a single sentence in a perfectly level voice, and the man signed a new contract with a hand shaking so badly the signature turned into a crooked line.

In the underworld, they no longer used his full name.

They called him “the Voss.”

Two words, enough to make every conversation in the room drop to a whisper. But every night, after Declan left, after the guards returned to their posts, after the penthouse at the top of Voss Tower sank into silence, Killian opened a door no one else was allowed to touch. Behind it was Rosalie’s bedroom.

When he moved into the penthouse in the fourth year after she vanished, he had transferred everything intact from the Gold Coast mansion.

The small bed. The butterfly sheets.

Mr. Honey, the stuffed bear.

The crayon drawing on the wall that said “Me and Daddy.” The fuzzy bunny slippers by the bed.

Nothing had been moved even an inch. The air in the room felt frozen in the moment eight years earlier when she had last slept there, and Killian wanted it that way. He stepped inside, closed the door, sat on the floor with his back against the bed in the same posture he had taken years before on the kitchen floor while Rosalie tied a bow in his hair, and he talked.

He told the emptiness about his day, about the weather, about the restaurant on Michigan Avenue earning a Michelin star, about how he still bought green grapes every week even though no one ate them.

“Daddy’s still looking for you, Rosie,” he would say. “Daddy hasn’t given up.

Daddy won’t ever give up.”

Then he would sit there in silence, eyes closed, staying until dawn crept close, before standing, closing the door, and returning to being the man the city knew. Declan Frost was the only one who knew about that room.

Not because Killian told him, but because one night Declan returned to the penthouse to retrieve forgotten files and heard Killian’s voice coming from behind the locked door.

He stood in the hallway and listened to his boss—the man the entire city feared—telling his daughter that today he had braided French braids for a little girl in the building who reminded him of her and how he still remembered how Rosalie used to tug on his sleeve when she wanted her hair fixed. Declan turned and walked away and never mentioned it. Down in the Gold Coast mansion Killian no longer lived in but still kept, Camille Ashworth existed like a ghost in her own home.

Killian didn’t divorce her and didn’t cast her out, but he rarely spoke more than ten sentences to her in a week.

She was allowed to stay, to eat, to be waited on, but not to leave the house beyond a radius Killian personally approved, always with one of Declan’s men nearby whenever she stepped outside. She was confined not with chains, but with the silence of a man waiting for her to expose herself.

Her body was betraying her long before her mouth ever could. The lupus progressed, attacking her kidneys, wearing her down.

She sat in the mansion, staring out the windows, day after day, rotting slowly under the weight of what she had done, while on the highest floor of Voss Tower, her husband sat on the floor of a preserved child’s room and spoke to the air.

Meanwhile, more than three hundred miles to the south, in Grafton, Illinois, another world existed—quiet, modest, and filled with a kind of light the big city could never hold. Iris Callaway was twenty-eight now, eight years after the night she waded into black water and pulled a child onto the bank. Her life had changed—not in a sudden miracle, but in the way a person clenches her teeth and climbs one step at a time while everything around her tries to drag her back down.

After leaving the Whitfield house that day, Iris had driven south for another two hours and stopped in a small town near St.

Louis. She waitressed for four months, cleaned motel rooms for three, then returned to Grafton because she realized she couldn’t go any farther from the child she had promised to come back to.

She rented a small room above an old bookstore on Grafton’s main street, paid part of the rent by helping clean the shop each morning, and worked nights at the only diner in town that stayed open until ten. A year later, she applied to the nursing program at Lewis and Clark Community College in Godfrey, a thirty-minute drive from Grafton.

She qualified for a Pell Grant because her income fell below the federal poverty line, covered the rest with financial aid and night shifts, and over four years, she didn’t miss a single class except for exams.

She passed the NCLEX on her first attempt and became a registered nurse at twenty-five. Now she worked the night shift at Grafton Community Hospital—twelve hours from seven in the evening to seven in the morning. She returned to her room at dawn, slept until noon, then woke to prepare food and drive to the Whitfield house.

Every week.

Without missing one in eight years. The promise she had made to Birdie on the day she left, she kept with every drive, every home-cooked meal, every afternoon spent on the Whitfield porch watching Birdie grow.

Birdie was fourteen now. She was no longer the six-year-old with empty eyes staring at birds through a window.

Now she was a quiet teenager—reserved, soft-spoken.

But when she did speak, each sentence carried more weight than her age suggested. Birdie loved to draw. She sketched river landscapes in pencil and watercolor: the surface of the water at dawn, sparrows perched on branches outside the window, Harold’s wooden boat tied at the dock.

Her paintings were calm and beautiful.

But June had noticed the same thing in every one of them for years now. Water was always there.

Rivers, rain, ponds, mist. As if water called to her and she didn’t know why.

At night, Birdie sometimes dreamed.

Not clear nightmares—just shapeless fragments. The sensation of falling. Wind.

Darkness.

Hands. She didn’t know whose hands they were.

Didn’t know whether they were holding on or letting go. Only that every time she woke from those dreams, she cried without understanding why.

When June heard her, she came into the room, sat beside the bed, stroked Birdie’s hair, and told stories until she fell asleep again.

Old stories, gentle stories, or tales June made up about a small bird flying through a storm and finding its way back to its nest. During the day, Harold taught Birdie different things. He taught her how to fish in the shallow bend of the river, how to tie boat lines, how to read the current to know where fish gathered and where hidden rocks lay.

He didn’t speak much.

Harold never had. But whenever Birdie asked a question, he answered with the patience of a man who understood that this child needed steadiness more than anything else.

Brier Whitfield, Harold and June’s twenty-year-old granddaughter, was the only person who made Birdie laugh out loud. Brier visited on weekends, dragged Birdie along the riverbank, caught fireflies at night, and talked endlessly about everything from movies to her college life and her boyfriend.

Brier was loud and bright, full of energy—the complete opposite of Birdie—and perhaps that was why they fit.

Birdie listened to Brier for hours without tiring, and Brier accepted Birdie’s silence without demanding explanations. Life in the Whitfield house was simple. Early mornings, Harold went to the river, and Birdie joined him when she wasn’t in school.

Afternoons, June cooked.

Evenings, Birdie drew on the porch. Nights, June told stories.

And every week, Iris arrived with food, medicine for the elders, and a tired but constant smile. To Birdie, Iris was “Sister Iris,” the only adult beyond her grandparents she trusted without question.

She didn’t know why Iris mattered so much.

She didn’t remember the night on the river. She didn’t remember the hands that pulled her from the dark water. But whenever Iris stepped onto the porch, something warm stirred in Birdie’s chest in a way she couldn’t explain—as if her body remembered something her mind had forgotten.

Beneath that peace, however, a question never disappeared.

Iris thought about it every night on the drive from the hospital back to her rented room. Harold and June mentioned it whenever Birdie had fallen asleep and they sat on the porch drinking tea in silence.

Where had the child come from? Who had done that to her?

Why had no one ever come looking for her?

Eight years and not a single person had appeared. No father. No mother.

No one.

As if Birdie had fallen from the sky and the river had simply delivered her to them. Iris didn’t believe that.

She knew the child hadn’t ended up in the river alone. Someone had put her there.

And one day, Iris feared, that person—or someone connected to them—might come back.

Paige Holloway wasn’t the kind of lawyer who sat in an office waiting for files to come to her. She was thirty-two, a graduate of the University of Chicago Law School—sharp, patient, and one of the very few people Killian Voss trusted, not out of fear but because of competence. Paige had begun working for Killian in the second year after Rosalie disappeared, when the third private investigation firm in a row reported no results and Killian needed someone with a legal mind to dig into corners ordinary investigators never touched.

For six years, Paige traced every possible path.

Coroner records across Illinois. Lists of unidentified children admitted to major hospitals in Chicago, Rockford, Springfield, and Peoria.

Adoption files through child services. Even new student registrations at elementary schools within a three-hundred-mile radius of Chicago that matched Rosalie’s age and description.

Nothing matched.

Or more precisely, Neil Ashworth had made sure nothing was allowed to match. But Neil Ashworth, powerful as he was, was still human. And the wall he built had a gap he never anticipated.

The rural health care system.

Small clinics in towns under a thousand residents often kept patient records on paper or on internal electronic systems not connected to the larger hospital networks. They sat outside the reach of centralized searches and beyond Neil’s focus because he had concentrated on blocking information at police levels and in federal databases.

He had never thought about a tiny clinic in a town he probably didn’t even know by name. Six months earlier, Paige had begun reviewing this system in a slow, methodical sweep, sending record requests to every clinic, every rural practice, every small community hospital along the lower Mississippi River and Illinois River, searching for any record of a child under ten admitted during the window when Rosalie vanished.

Most replies yielded nothing.

Until an envelope from Grafton Community Health Clinic arrived at her office on a Tuesday afternoon. Inside was a photocopy of a handwritten medical record. The paper was slightly yellowed with age, bearing an admission date that matched the night Rosalie disappeared exactly.

Patient: female child.

Estimated age: six. Identity: unknown.

Symptoms: head trauma, hypothermia, water in lungs, memory loss. Brought in by young woman, full identity not provided, stated she found patient drifting in river.

Blood type: B positive.

Identifying marks: small crescent-shaped scar on left side of forehead. Paige reached the last line and stopped. She opened Rosalie Voss’s original file—the one she always carried in her briefcase.

Blood type: B positive.

Crescent-shaped scar on left forehead from a fall down the stairs at age four. Her hands shook.

She read it again, then again. Then she picked up the phone and called Killian.

He answered on the first ring, the way he always did when Paige called, because Paige never called without reason.

She spoke slowly and clearly, one word at a time, explaining that she had found a medical record at a clinic in Grafton, Illinois, roughly three hundred miles south of Chicago, documenting a female child about six years old, admitted on the exact night Rosalie disappeared. Head injury. Amnesia.

Pulled from a river.

Matching blood type. Matching forehead scar.

Silence followed. Paige heard Killian’s breathing on the other end, heavier than usual, then no breath at all for three seconds, as if he had forgotten how to breathe.

Then Killian asked, in a voice unlike the flat, controlled tone she had known for six years—a voice of a man struggling not to break apart:

“Who brought her in?”

Paige replied that the record listed a young woman, identity incomplete, no contact information, but that she could go to Grafton in person, trace the clinic trail, and find her.

Killian said nothing for five seconds. Then, for the first time in eight years, Paige heard something in his voice she hadn’t believed he could still feel. Hope.

“Find that woman,” he said.

“Find her at any cost.”

Killian didn’t wait until morning. Two hours after Paige’s call, he was already in a black Escalade racing south on Interstate 55 out of Illinois.

Declan drove; a security SUV followed behind. Paige had sent him the address of the Grafton clinic, the name of the night-duty doctor from eight years earlier, who had since retired, and the most critical detail of all: the young woman who had brought the child in that night likely still lived in the area because temporary guardianship records from child services listed a witness named Iris Callaway who had signed to confirm when the Whitfields took the child in.

Paige dug further.

Iris Callaway, twenty-eight, registered nurse, currently working the night shift at Grafton Community Hospital. Killian read that message on his phone and stayed silent for the entire four-hour drive. Declan had known his boss long enough to understand that when Killian went quiet like this, it wasn’t calm.

It was restraint of the most dangerous kind—the kind that held everything inside because if it broke loose, it might never be contained again.

The convoy reached Grafton at 1:45 in the morning. A town of fewer than seven hundred people.

Streets swallowed by darkness. Only a few weak yellow streetlights and the muted sound of the Mississippi moving somewhere unseen.

Two glossy black SUVs parked in front of the community hospital like shadows that had wandered into the wrong place.

Killian stepped out. Declan followed. The guards stayed behind by order.

At night, Grafton Community Hospital had one nurse on duty, one doctor available on call from home if needed, and pale fluorescent lights stretching down mostly empty hallways.

Killian pushed the door open at two in the morning. The sound of leather shoes echoed on tile.

Iris Callaway sat at the nurse’s station at the far end of the hall, hair tied high, light-blue scrubs on, charting patient notes. She looked up at the sound of footsteps and saw a tall man in a black suit walking toward her with the stride of someone used to the world clearing a path.

Behind him was another man, taller, broader, keeping three steps back like a shadow.

Iris set down her pen and stood. Her instincts, sharpened by twenty-eight years of surviving difficult people and dangerous situations, told her this man was not a patient, not family, and not someone who belonged in a rural American hospital at two in the morning. “How can I help you, sir?” Iris asked, her voice steady, her eyes never leaving his.

Killian stopped at the counter and looked at her.

He wasn’t used to being met with an unflinching gaze, but this woman in front of him was doing exactly that. “Are you Iris Callaway?” Killian asked.

Iris’s eyes narrowed slightly. “Who’s asking?”

“My name is Killian Voss.

I’m looking for information about a child brought to a clinic in this area eight years ago.

A girl about six years old. Head injury. Memory loss.

Pulled from the river.”

Iris’s heart skipped a beat, but her face didn’t change.

She knew instantly who he meant. For eight years, she had both waited for and feared this moment—the moment someone would come asking about the child.

She didn’t let that fear show. “Why are you looking?” she asked.

“Because she’s my daughter.”

Silence settled between them.

Iris studied him, measuring every line of his face, searching for lies, for danger, for anything that would give her a reason not to believe him. “Do you have proof?” she asked plainly. Killian wasn’t used to being asked to prove anything.

In his world, he spoke and people believed him or pretended to because they were afraid.

But he reached inside his jacket and placed an envelope on the counter. Inside were photographs of Rosalie at five years old, the original birth certificate stamped by Cook County, and medical records documenting her blood type.

Iris opened the envelope and examined each page slowly and carefully. She looked at the photo of the curly-haired child smiling wide and saw Birdie there—the same lines of the face, the same eyes, the same curve of the mouth.

Her chest tightened, but she said nothing.

She closed the envelope, set it down, and met Killian’s eyes. “Even if she is your daughter, I need to know why a six-year-old child ended up floating in a river in the middle of the night,” Iris said, “and why no one came looking for her for eight years.”

Killian stood still. The question struck directly into the deepest wound he had carried all this time.

“I did look,” he answered in a voice lower than usual.

“Every day for eight years. Someone stopped me.”

Iris didn’t nod or shake her head.

“I don’t know who you are beyond the name on that birth certificate,” she said. “I don’t know if you’re here out of love or for some other reason.

And until I’m certain, I won’t tell you anything about that child.”

Declan took a step forward out of habit, ready to protect his boss when someone dared refuse him.

Killian raised a hand to stop him without turning his head. Iris glanced at Declan, then back at Killian. “You can buy this entire town,” she said quietly.

“But you can’t buy my trust.

If you want my help, you come alone. No guards.

No pressure. No threats.

You come as a father, not as whatever you are out there, and I’ll decide for myself whether that child is safe with you.”

Killian looked at her.

In eight years, no one in his life—not Declan, not Paige, not an enemy or an ally—had spoken to him that way. And the person doing it wasn’t a rival boss, not a politician, not a lawyer, but a night-shift nurse in a town of seven hundred people, barely over five feet tall, thin, with dark circles under her eyes, standing in light-blue scrubs and refusing to bend. “All right,” Killian said.

Declan turned to look at him.

In ten years of working for Killian Voss, it was the first time Declan Frost had ever seen his boss yield to anyone. The next day, exactly as Iris had demanded, Killian came alone.

No Declan. No guards.

No black SUVs.

He rented an ordinary sedan from the town’s only motel and followed Iris’s directions along the dirt road that ran beside the river toward the Whitfield house. Iris sat in the passenger seat and said nothing during the fifteen-minute drive. She had called Harold and June the night before and told them everything: that a man had come asking about Birdie, that he claimed to be her biological father, that he had documents and photographs, and that Iris believed he was telling the truth—but needed them to meet him before any decision was made.

June had cried on the phone.

Harold had been silent for a long time, then said only, “Bring him here. I’ll know by looking in his eyes.”

Killian stopped the car about fifty meters from the house because the dirt road was too narrow to go farther.

He stepped out and looked straight ahead. A small, one-story wooden house with weathered white paint, a gray tin roof, a wide porch with two old wooden chairs, and a child sitting on the porch steps with a sketch pad in her lap and a pencil in her hand.

Killian stopped moving.

The girl was fourteen, brown curls falling over her shoulders, head bent in concentration over her drawing. She didn’t hear the car. She didn’t know someone was standing fifty meters away looking at her as if at a miracle.

Killian didn’t move.

His eyes locked onto the child. Brown curls like Margot.

The curve of her cheekbones like Margot. But the way the girl frowned when she concentrated, the angle of her head, the eyes when she lifted them to follow birds flying past—those were his eyes.

Eight years crashed into him all at once.

He didn’t fall. His legs simply buckled slowly, the way a body collapses when it can’t carry the weight of what it feels. Iris reached out to steady him, but she was much smaller and could only grip his arm so he didn’t drop all the way to the ground.

Killian dropped to one knee on the dirt road, one hand braced in the dust, and made no sound.

He cried without sound. Tears fell without sobs, without broken breaths, only silence and tears—the kind that come from a man who forgot how to cry long ago and whose body remembers only the tears.

Birdie looked up. She saw a stranger kneeling in the dirt road and a familiar woman standing beside him.

“Sister Iris,” she called, standing up, her voice worried.

“What’s wrong with him?”

Iris walked up onto the porch, sat beside Birdie, and wrapped one arm around the girl’s shoulders. “He’s come a very long way to be here,” Iris said softly. “I need to tell you something.”

Birdie looked at Iris, then at the man struggling to stand, wiping his face with the back of his hand and trying to walk toward the porch on unsteady legs.

In Birdie’s eyes was the fear any child feels when seeing an adult cry—especially a stranger looking at her as if she were the most precious thing in the world.

At that moment, the front door opened. Harold stepped out first, his back straighter than usual, his gaze fixed on Killian below the porch.

June followed, her hands clasped tight at her chest, eyes already red. Harold looked at Killian in silence—the way an old man measures a younger one by the only measure he truly trusts: the eyes.

Killian met Harold’s gaze without hiding anything.

His eyes weren’t the eyes of a boss, not of a CEO, not of the darkness Chicago feared. They were the eyes of a father who had just seen his daughter after eight years and was doing everything he could not to collapse again. Harold nodded once, as if he had seen enough.

Iris looked at Birdie, took her hand, and said, “This man is your biological father, Birdie.

He’s been looking for you for a very long time.”

Birdie looked at Killian, eyes wide, not understanding, not remembering—but no longer afraid. She studied him for a long moment, then asked in a small voice, “How long have you been looking for me?”

Killian opened his mouth, but no sound came.

He swallowed once, then again, and finally spoke, his voice shaking so badly each word seemed pulled from his chest. “Every day for eight years,” he said.

“Every single day.”

Birdie said nothing.

She looked down at Killian’s shoes, dusty from the road, at his hands still marked with earth from where he had knelt, at his eyes red and wet, and she whispered, “I don’t remember you. I’m sorry.”

Killian shook his head. “You don’t have to remember me,” he said.

“I just need to know you’re alive.

You being alive is enough.”

June stepped down from the porch, tears flowing freely now. Harold stood beside her, holding her hand.

Killian turned to them and did something no one in his empire had ever seen him do. He dropped to both knees in front of the two elders.

“Thank you,” he said, his voice breaking.

“Thank you for saving my daughter. Thank you for raising her. Thank you for giving her a life I couldn’t give her for eight years.

I owe you a debt I can never repay.”

Harold stepped forward, bent down, grasped Killian’s arms with surprising strength, pulled him to his feet, and said in a rough, low voice, “Stand up, son.

We don’t need repayment. We only did what our hearts told us to do.”

Then he turned toward the house.

“Open the door,” he called. “Come inside, all of you.

Standing out here in the cold wind isn’t good.”

Killian didn’t return to Chicago.

That night, he called Declan and said two sentences. “I’m staying here. You handle everything back home.”

Declan didn’t ask how long.

He knew the answer would be: until I decide to come back.

The only hotel in Grafton was a two-story roadside inn with ten rooms on the main street, the kind where the bed creaked when you turned and the hot water lasted only fifteen minutes. Killian rented the largest room—which was barely wider than the others—set his laptop on an old wooden desk, and turned it into a remote command center for his empire.

Every morning, he spoke with Declan by phone, reviewed contracts by email, and made decisions for a network stretching from the South Side of Chicago to Indiana through brief calls that never lasted more than three minutes. The rest of the day, he gave to Birdie.

But he didn’t rush.

Iris told him from the beginning that he couldn’t force a fourteen-year-old girl who had no memory of him to call him Dad within a week, that he had to let her adjust. Killian listened. He followed her advice, something that surprised even himself—because he wasn’t a man accustomed to following anyone.

On the first day, he went to the Whitfield house and simply sat on the porch three meters away from Birdie in silence while she drew.

Birdie glanced at him a few times, said nothing, and went back to her sketching. The second day was the same.

On the third day, Birdie asked if he liked drawing. Killian answered honestly that he didn’t know how.

Birdie looked at him for a moment, tore a sheet from her sketch pad, handed it to him with a pencil, and said, “Then you should practice.”

Killian held the pencil for the first time in years, not to sign contracts or approve orders, but to draw a bird that came out looking more like a chicken.

Birdie looked at the drawing and didn’t laugh, but the corner of her mouth twitched. That was the first step forward. On the fifth day, Harold invited Killian to go fishing.

Killian had never held a fishing rod in his life, but he sat in the old wooden boat in the middle of the Mississippi River with Harold and Birdie from morning until noon, caught nothing, and still understood that this was the first time in eight years he had felt something close to happiness.

Iris watched it all. She wasn’t always there—her twelve-hour night shifts took her mornings for sleep—but every afternoon she came to the Whitfield house, and she saw everything.

She saw Killian sit for hours by the river watching Birdie fish without impatience, without checking his phone, without pacing the way men used to controlling everything often did. She saw him hold the drawing Birdie gave him with both hands, careful and gentle, as if it were more valuable than any contract he had ever signed.

She saw him listen to Harold’s stories without interrupting, nodding in the right places, asking simple questions.

And she began to see something she hadn’t expected. That beneath the darkness this man carried, there was something still intact—buried deep, but not dead. Like the roots of a burned tree still alive underground.

Killian watched Iris, too.

Not intentionally at first, but gradually he couldn’t help it. He saw her work twelve-hour night shifts, return to her rented room at dawn, sleep until noon, wake to cook, then bring food to the Whitfield house every afternoon—containers of soup, trays of lasagna, homemade bread.

She didn’t have much money. He knew that.

The small room above the old bookstore.

The old pickup truck. The narrow rotation of clothes. Yet every week she still brought food to the Whitfields, bought medicine for Harold when his back hurt, bought new sketchbooks for Birdie when the old ones ran out.

She gave everything she had while keeping almost nothing for herself.

Killian didn’t understand that. In his world, people gave to get something back.

Every favor had a price. Every kindness was an investment.

But Iris Callaway gave without expecting anything.

She did it because she wanted to. Because she loved these people. Because she didn’t need repayment.

Killian didn’t know what to call the thing stirring in his chest when he watched her, but it was there, smoldering, growing heavier by the day.

There were small moments they both pretended not to notice. One afternoon, Iris made coffee in the Whitfield kitchen, poured three cups for Harold, June, and herself, then automatically poured a fourth no one had asked for and set it at the corner of the table where Killian usually sat.

She said nothing. He said nothing.

He drank the cup.

One morning, Iris finished her shift at seven, stepped out of the hospital into the pale early light, and saw the rental car Killian was using parked in the lot. He sat inside with the window halfway down, reading something on his phone. When he saw her, he didn’t wave or call out.

He simply started the engine and followed her slowly along the road from the hospital to her rented room, waiting until she unlocked the door and went inside before turning around and leaving.

Iris didn’t ask why he was there. He didn’t explain.

The next day, he was there again. And the day after that.

Neither of them spoke about it.

But every morning, when Iris stepped out of the hospital and saw the familiar car parked at the edge of the lot, something warmed in her chest in a way she wouldn’t let herself name. Because she knew who he was. She knew the world he came from.

And she knew that allowing herself to feel anything for him meant stepping into a place she might not be able to leave.

The incident happened on the twelfth night after Killian arrived in Grafton. Around one in the morning, a male patient was rushed into the emergency room—heavily intoxicated, his arm cut by broken glass from a bar fight, blood soaking his sleeve.

Iris was the only nurse on duty. She placed him on the bed and began disinfecting the wound, but he jerked his arm away, cursed, and suddenly swung his fist.

The punch landed squarely on Iris’s face, right at her mouth.

She fell backward into the instrument cart, stainless steel trays crashing loudly onto the floor. Her lower lip split open. Blood ran down her chin.

The night security guard rushed in, dragged the man back, and cuffed him to the bed.

Iris stood up, wiped the blood from her lips with the back of her hand, finished treating the patient as if nothing had happened, then walked into the nurse’s room and closed the door. She sat down, opened the medicine cabinet, took out a suture needle, a roll of surgical thread, and a small mirror.

She propped the mirror on the table, tilted her head so the fluorescent light fell on the tear in her skin, and began stitching it herself. Her hand shook—not from pain; Iris handled pain better than most people—but from exhaustion.

The kind that came from twelve-hour night shifts, from eight years of being alone, from a lifetime of having no one show up when she was hurt.

She pushed the needle through skin, clenched her teeth, pulled the thread tight, and was preparing the second stitch when the door opened. Killian stood in the doorway. He had come to the hospital at three in the morning every night, parking at the edge of the lot to wait for Iris’s shift to end.

Tonight, he had seen the ambulance, seen security hauling a drunk man down the hall, and walked inside.

Someone pointed him toward the nurse’s room. He pushed the door open and saw Iris sitting alone under the harsh white light, blood on her chin, needle in her hand, stitching her own lip with no one helping her, no one asking if she was okay, no one even realizing she was injured.

Killian said nothing. He stepped in, pulled up a chair, sat across from her, and held out his hand—not to grab the needle, just held it out, palm up, resting on the table between them.

Iris looked at his hand: large, calloused at the knuckles, clean but not soft, the hand of a man who had carried more weight than most people ever would.

Then she looked at his face. Killian didn’t tell her to put the needle down. He didn’t insist on helping.

He simply sat there, hand extended, eyes on her, and waited.

Iris set the needle down. She didn’t cry.

“I’m used to it,” she said quietly, her voice as flat as if she were talking about the weather. Killian looked at her—the blood on her chin, the dark circles under her eyes, the half-stitched lip, the scrub top speckled red—and heard those three words.

I’m used to it.

Words carrying the weight of twenty-eight years of being hurt, abandoned, wounded, then standing back up alone. “No one should ever be used to this,” he said very quietly. Iris looked at him—and for the first time since the night he walked into the hospital corridor at two in the morning, she didn’t look at him with caution.

She looked at him with something else.

Something she had kept locked away for years because every time she let it surface, the world took it from her. Trust.

Killian called the on-call doctor to finish suturing Iris’s wound. He sat beside her until it was done, then drove her back to her rented room.

She opened the car door, paused, didn’t turn around, only said, “Thank you,” and stepped out.

Killian sat in the car, watching the light come on in her room above the old bookstore, and stayed there for a long time before driving away. That same night, more than three hundred miles north of Grafton, Declan Frost called Killian at five in the morning. Declan’s voice sounded no different than usual—calm and precise—but Killian heard what others wouldn’t.

Urgency.

“Tobias Kane is probing,” Declan said. Tobias Kane, forty-three years old, controlled a major part of the narcotics trade in northern Chicago from Rogers Park down to Lakeview.

He had been Killian’s biggest rival for five years. Killian’s prolonged absence from Chicago hadn’t escaped Tobias’s notice.

He had sent people to investigate, and his people had found Grafton.

Declan reported that two days earlier, a truck with Illinois plates had been parked outside the Whitfield house at eleven at night, taking photos, then driving off. “My people traced the plate,” Declan said. “Rental under fake papers.

The line leads back to Kane’s crew.

I’ve handled that part. The truck is gone.

The driver is no longer anywhere near Illinois. But Kane knows you’re there now.

And he knows why.”

Killian sat on the bed in the Grafton motel, phone to his ear, staring out the window at the sky slowly brightening over the small town he had lived in for twelve days—a town of seven hundred people, dirt roads, wooden houses, an old bookstore, a community hospital, elderly couples fishing by the river, a child drawing on a porch, and a night-shift nurse stitching her own wound alone.

And now, because of him, Tobias Kane knew this place existed. Because of him, these people had become potential targets. Killian understood better than anyone that his darkness didn’t stop at his doorstep.

It followed him.

Clung to him. And anyone who stood close to him long enough was touched by it.

He had brought that darkness into the most peaceful place he had ever known, and he didn’t know how to take it away without taking himself with it. The accident happened on a Saturday afternoon, three days after the night Iris was assaulted at the hospital.

Brier came to visit her grandparents for the weekend as usual and dragged Birdie down to the riverbank to “catch fireflies,” even though it was still daylight.

“Evening fireflies are different from night fireflies,” Brier insisted, and Birdie didn’t bother arguing; arguing with Brier was the most pointless thing in the world. The two of them walked along the river to Harold’s dock, where the old wooden boat was tied with a rope looped around a weathered post. Brier climbed onto the boat first.

Birdie followed.

The riverbank was still damp from the rain the night before. Moss slicked the rocks and wood.

When Birdie stepped onto the edge of the boat, the sole of her shoe slipped on the wet wood. She lost her balance, tipped sideways, and her right temple struck hard against the rim of the boat.

The sound was dull and brief.

Birdie fell into the shallow water by the shore and lay still, eyes closed, unmoving. Brier screamed. The scream carried to the Whitfield house less than a hundred meters away.

Harold ran out first, shockingly fast for a man in his seventies.

June followed. Killian had been sitting on the porch reading emails when he heard the scream.

His reaction was faster than thought. He ran faster than Harold, faster than anyone, reaching the river in seconds.

Birdie lay in the shallows, water halfway up her body, her head tilted to one side, blood seeping from a cut on her temple and mixing into the muddy water.

Killian plunged down, lifted her from the water, and laid her on the grass. His face went pale. His hands shook as he checked her breathing.

Birdie was breathing—but unconscious.

Iris arrived ten minutes later. She’d been asleep in her rented room after a night shift when Harold called.

She drove over with her hair uncombed and eyes barely awake, but her hands were steady the moment she touched Birdie. She checked pupils, tested reflexes, pressed gently around the head wound, then said they needed to go to the hospital immediately.

It could be a concussion.

Killian carried Birdie to the car. Iris sat in the back seat, stabilizing the girl’s head. Harold and June followed in their own car.

Brier cried nonstop in the passenger seat.

Grafton Community Hospital, the same hospital where Iris worked nights, took Birdie into the emergency room. The doctor ordered imaging and examined her.

A mild concussion. A superficial laceration.

No internal bleeding.

Birdie needed observation and rest. Killian sat beside the bed and didn’t move, both hands holding one of Birdie’s, his eyes fixed on her face. He couldn’t breathe evenly until the doctor said she was out of immediate danger.

Birdie was unconscious for four hours.

When she opened her eyes, it was dark outside. Pale white light filled the hospital room.

Killian was still there, his hand still wrapped around hers. Iris stood at the foot of the bed.

Harold and June sat in the hallway.

Birdie blinked, looked at the ceiling, then turned her head toward Killian. And in that moment, her eyes changed. Not gradually.

Abruptly.

As if someone had flipped a switch in a room sealed for eight years. Her eyes widened.

Her pupils dilated. Her whole body went rigid.

She stared at Killian as if seeing a ghost.

Then she smelled coffee—not hospital coffee, but coffee from a kitchen with marble floors in Chicago, brewed at five in the morning, mixed with the smell of pancakes and star-shaped slices of banana. She heard a man’s low voice singing a lullaby every night, a tune she couldn’t name but remembered every note of. She saw a room with butterfly sheets, Mr.

Honey the teddy bear, a crayon drawing on the wall.

She saw a mansion, stairs, a garden filled with flowers, a purple plastic cup. And then she saw the bridge.

Darkness. Cold wind.

Hands gripping her wrists.

And then letting go. The sound of water. The memories didn’t return in gentle fragments.

They crashed back all at once.

Like a dam breaking. Like a flood with no warning.

Eight years of memory locked behind an injury surging back in seconds. Birdie screamed.

It wasn’t the scream of a child in physical pain.

It was the scream of someone who had just remembered she almost died. “Daddy!” she cried, eyes locked on Killian. It was the first time that word had left her mouth in eight years.

“Daddy, I remember now.

I remember everything. My name is Rosalie.

Daddy… she dropped me in the river. She let go of me.”

Killian stopped breathing.

He sat there holding his daughter’s hand, hearing the words he had waited eight years for and feared more than anything.

She remembered. She remembered everything. And she remembered who had done it.

He pulled Rosalie into his arms.

She clung to him, shaking, sobbing, her whole body trembling. He cried—not silently like on the dirt road outside the Whitfield house.

This time he cried out loud. The sobs of a man whose restraint shattered after eight long years, in a small hospital room in a town of seven hundred people.

Father and daughter held each other on the hospital bed, and no one in the room dared speak.

In the hallway, Harold leaned against the wall, one hand covering his eyes. June sat on a plastic chair, both hands over her face, shoulders shaking. Brier stood beside her, crying too, even though she didn’t fully understand what was happening.

In the corner of the room, Iris Callaway stood with her back against the wall, arms hanging at her sides, tears streaming down her cheeks without her wiping them away.